E&M

2020/2

Un declino annunciato e le strategie dei quotidiani

Negli anni Novanta e nei primi anni Duemila, la maggioranza degli editori e dei quotidiani adottarono lo stesso modello di business della televisione commerciale: i contenuti pubblicati divennero fruibili a tutti a titolo gratuito e si decise che i ricavi digitali sarebbero derivati solo dalla raccolta pubblicitaria. Inoltre, a parte alcune eccellenze internazionali il rapporto tra sfruttamento del supporto cartaceo ed esplorazione del supporto digitale è stato gestito con difficoltà da quasi tutti gli editori. Tra i possibili sviluppi futuri del settore, emerge la possibilità di riposizionare il prodotto-quotidiano verso l’alto, abbandonando la «popolarizzazione» avviata nel corso degli anni Novanta del secolo scorso, e sviluppare una logica commerciale che tenga conto del riequilibrio intervenuto tra mercato dei lettori e mercato pubblicitario.

La crisi dei quotidiani ha generato un ampio dibattito a livello giornalistico[1] e accademico[2] che ruota intorno alle seguenti domande: i quotidiani sopravvivranno? Se sì, in che forma? Se no, quali saranno le conseguenze per il settore e per i sistemi democratici[3]?

Per rispondere a queste domande è necessario tornare indietro alla metà degli anni Novanta, quando i quotidiani decisero di diversificarsi e di affiancare, al tradizionale supporto cartaceo, quello digitale[4]. I giornali avrebbero potuto rapportarsi a internet in tre modi: decidendo di resistere al web e rimanere off-line – e, quindi, non pubblicare i propri contenuti in digitale; decidendo di abbracciare la nuova tecnologia e di pubblicare on-line i propri contenuti a titolo gratuito o a pagamento. Inoltre, in tutti e tre i casi avrebbero potuto fare pressioni affinché le autorità politiche regolamentassero la diffusione di contenuti informativi attraverso internet[5].

Il «peccato originale» degli editori

I first mover e i leader di mercato (per esempio, The New York Times negli Stati Uniti e la Repubblica in Italia) decisero fin da subito di abbracciare la nuova tecnologia e, in questo abbraccio, imitarono il modello di business della televisione commerciale, ossia decisero di diversificare pubblicando i propri contenuti a titolo gratuito basando i ricavi digitali solo ed esclusivamente sulla raccolta pubblicitaria. Inoltre, non esercitarono pressioni affinché internet fosse in qualche modo regolamentata. Questa mossa contribuì a rendere l’accesso gratuito la norma e lo standard per il settore, vincolando anche il comportamento degli altri quotidiani e dei follower (solo pochi quotidiani deviarono da questa strategia, come, per esempio, il Wall Street Journal). La decisione fu presa per poter sfidare finalmente la televisione sul suo stesso terreno, ossia quello dell’immediatezza dell’informazione e della raccolta pubblicitaria[6]. I quotidiani, a questo punto, avrebbero potuto puntare sulla differenziazione del proprio prodotto, sia rispetto alla televisione, sia rispetto a quanto offerto da tutti gli altri attori che iniziavano a nascere e a diffondersi su internet e a caratterizzarsi come editori digitali puri. L’obiettivo dei quotidiani tradizionali era quello di utilizzare internet per allargare il proprio mercato potenziale, aggiungendo ai lettori-acquirenti dell’edizione cartacea i lettori-consumatori dell’edizione digitale, e agli investitori pubblicitari dell’edizione cartacea gli investitori pubblicitari dell’edizione digitale. Il prodotto digitale avrebbe dunque dovuto essere complementare rispetto all’edizione cartacea. Sostanzialmente, però, non solo imitarono il modello di business della televisione commerciale, ma anche i contenuti e la forma, rendendo scarsamente differenziati i propri prodotti rispetto a quelli della televisione e degli altri attori presenti su internet.

La crisi prima di internet

Questa strategia di imitazione, però, non dipese solo dalla diversificazione imposta da internet, ma da un processo iniziato prima e che si è sviluppato in parallelo. Questa situazione la si è osservata in particolare nel nostro Paese.

In Italia, a differenza di altri Paesi, i quotidiani non hanno mai raggiunto una penetrazione di massa e non si è mai affermata una chiara e netta distinzione tra «quotidiani di qualità» e «quotidiani popolari»[7]. Inoltre, dopo il picco di copie vendute raggiunto nel 1990[8] si è osservato un progressivo calo (che si è poi trasformato in repentino tracollo)[9]. Per rispondere a questa situazione, i quotidiani decisero di posizionarsi maggiormente verso la dimensione «popolare», un’impostazione editoriale che influì sia sul contenuto sia sullo stile grafico[10]. Per quanto riguarda i contenuti, i quotidiani decisero di ampliarne la varietà mischiando sempre più temi «alti» e «bassi», hard e soft news, argomenti seri e argomenti frivoli. Si assistette inoltre a un aumento degli inserti e dei supplementi, tra cui è il caso di citare quelli destinati alle lettrici (per esempio, Io Donna del Corriere della Sera e D - la Repubblica delle Donne, lanciati entrambi nel 1996)[11]. Lo stile grafico vide l’introduzione progressiva del colore e un uso più estensivo delle immagini. Inoltre, furono prese decisioni per supportare i ricavi e per contenere i costi. Per quanto riguarda i primi, i quotidiani aumentarono il prezzo di vendita (variandolo in funzione della presenza o meno di inserti e supplementi), e abbinarono alle copie cartacee prodotti collaterali (prima VHS poi DVD, libri ecc.). Sul fronte dei costi, si puntò a incrementare l’efficienza dei processi editoriali e dei processi produttivi con l’adozione di nuove tecnologie e riduzione del personale. La decisione di abbinare la vendita di prodotti collaterali a quella del quotidiano rese quest’ultimo non più l’oggetto finale di una scelta, ma un mezzo per acquistare qualcos’altro a un prezzo più basso o, nel caso dei prodotti audiovisivi, per accedere a un altro media. Pertanto, quando iniziò a diffondersi internet i quotidiani stavano già attraversando una situazione di crisi e vedevano nella rete lo strumento per poter fronteggiare le difficoltà in cui si trovavano e riequilibrare lo svantaggio rispetto alla televisione[12].

La crisi dopo internet

Il progressivo sviluppo delle infrastrutture di rete e del web, la proliferazione dei dispositivi utilizzati per accedere a internet (computer, smartphone, tablet), la nascita e lo sviluppo di nuovi attori e prodotti (le piattaforme algoritmiche, le piattaforme di messaggistica istantanea ecc.), abbatté definitivamente i confini tra i settori e le imprese: tutti i media (testate giornalistiche, televisioni, radio, social network) sono contemporaneamente in concorrenza gli uni con gli altri, 24 ore al giorno, 7 giorni su 7, per soddisfare i bisogni di informazione e di intrattenimento delle persone (lettori, ascoltatori, spettatori). Questa situazione non ha fatto che accentuare la crisi dei quotidiani.

Focalizzando l’attenzione sul lato dell’offerta, possiamo spiegare le ragioni della crisi ricorrendo all’ormai classico modello sfruttamento-esplorazione[13]. Gli editori di quotidiani, al di là dei proclami ufficiali, decisero che il supporto cartaceo era destinato a morte sicura[14], e decisero pertanto di sfruttarlo come semplice cash cow, limitando al minimo le risorse e le competenze per il suo mantenimento e sviluppo. Ne è un esempio il fatto che non vi siano state innovazioni di rilevo sul fronte della distribuzione fisica del prodotto e nella rete delle edicole. Contemporaneamente, gli editori esplorarono internet per sviluppare nuovi prodotti, nuovi servizi e nuovi mercati. Come già scritto, questo è stato però fatto imitando gli altri media e gli altri attori. Anzi, a seguito dell’evoluzione tecnologica la strategia di imitazione è stata portata alle estreme conseguenze: al testo scritto non solo sono state aggiunte le immagini, ma anche i prodotti audio (i podcast), i video e le web TV, incrementando, quindi, la sovrapposizione con la radio e la televisione; la popolarizzazione dei contenuti si è accentuata ed è andata di pari passo con il sensazionalismo del tono, e in particolare relativamente ai contenuti pubblicati sul sito web e distribuiti attraverso i social media (si pensi ai video dedicati agli animali domestici, alle cose strane dal mondo ecc.). In questo modo, si è creata una crasi tra il prodotto distribuito su carta e quello distribuito via web (il pubblico è differente, ma la testata è la stessa) con conseguente confusione tra contenuti editoriali/giornalistici e contenuti generati dagli utenti. Infine, all’informazione per così dire classica si è aggiunto un forte appartato di comunicazione con lo sviluppo di servizi di native adverstising, native content, branded content, marketing content ecc., generando in questo caso commistione (e confusione) tra contenuti giornalistici e contenuti pubblicitari.

Tra carta e digitale, tra lettori e pubblicità

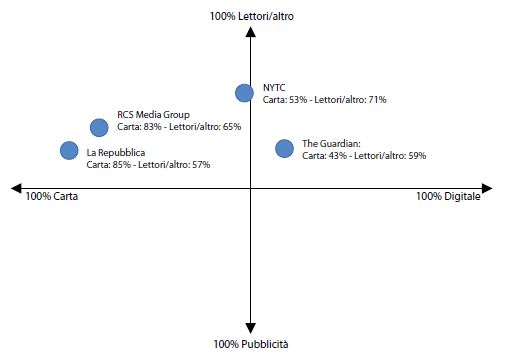

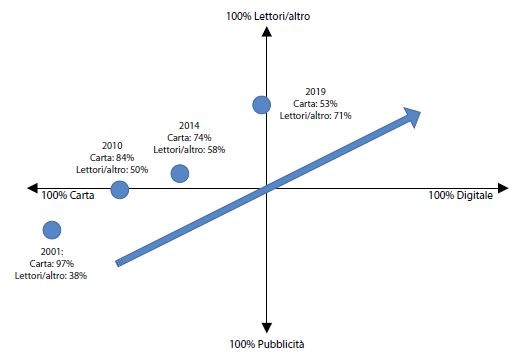

Quanto fin qui descritto è avvenuto in un contesto di progressiva riduzione delle risorse derivanti sia dalla vendita dei prodotti editoriali sia da quella degli spazi pubblicitari[15]. È importante focalizzare l’attenzione sulle risorse a disposizione dei quotidiani e sulle fonti di queste. Possiamo distinguerle per supporto (carta o digitale) e per cliente (i lettori o gli investitori pubblicitari). Confrontiamo tra loro i seguenti editori/quotidiani: RCS Media Group, GEDI (la Repubblica), The New York Times Company e The Guardian Media Group (The Guardian) e posizioniamoli in uno spazio delimitato in orizzontale dal supporto (carta o digitale) e in verticale dal cliente (lettori/altro o investitori pubblicitari)[16]. La Figura 1 mostra il posizionamento di questi quattro editori/quotidiani nel 2019[17]: i ricavi di RCS Media Group derivano per l’83 per cento dalla carta di cui il 65 per cento dai lettori o da altre forme di introito; quelli di GEDI (la Repubblica) per l’85 per cento dalla carta di cui il 57 per cento dai lettori/altro; il New York Times deriva il 53 per cento dei ricavi dalla carta di cui il 71 per cento dai lettori/altro; per il Guardian il 43 per cento dei ricavi derivano dalla carta di cui il 59 per cento dai lettori/altro. Focalizziamo l’attenzione sul New York Times per il quale si hanno a disposizioni dati longitudinali affidabili. Il suo modello di business è notevolmente cambiato negli ultimi 20 anni (Figura 2): nel 2001 la carta contava per il 97 per cento dei ricavi e dai lettori era generato il 38 per cento dei ricavi. Il peso della carta si è ridotto e il peso dei lettori è aumentato. Il tutto è avvenuto in particolare negli ultimi 5 anni. Cosa ci dicono questi dati? I dati ci dicono che la carta è ancora il supporto più importante: è importantissimo per RCS Media Group e per GEDI dove oltre l’80 per cento dei ricavi derivano da questo supporto. La carta è ancora importante per il New York Times perché è ancora il supporto prevalente. La carta è meno importante per il Guardian anche se è ancora rilevante rappresentando, in ogni caso, il 43 per cento dei ricavi.

Figura 1 – Il posizionamento di alcuni editori/quotidiani

Figura 2 – L’evoluzione del modello di business del New York Times

Inoltre, i ricavi derivanti dai lettori sono prevalenti per tutti gli editori/quotidiani presi in considerazione: si va da un minimo del 57 per cento di GEDI (la Repubblica) a un massimo del 71 per cento per il New York Times. Al di là del supporto considerato, quindi, è cambiato e sta cambiando il modello di business e diventa sempre più importante la propensione a pagare da parte del lettore. Per la carta questa non è una novità perché la cosiddetta free press è sempre stata presente ma minoritaria. Uno studio[18] condotto sul mercato statunitense ha rilevato che, pur in presenza di un elevato aumento del prezzo delle copie singole e degli abbonamenti (il prezzo delle copie singole nel periodo 2008-2016 è triplicato, quello degli abbonamenti è aumentato in media di 293 dollari), due terzi dei lettori sono rimasti fedeli al proprio giornale confermando, quindi, la relativa inelasticità della domanda all’aumento del prezzo. Per il digitale la situazione è invece differente. Negli anni Novanta e nei primi anni Duemila, la decisione presa a livello globale dalla maggioranza degli editori e dei quotidiani di adottare il modello di business della televisione commerciale ha reso l’informazione una commodity e, quindi, ha inciso negativamente sulla propensione a pagare da parte dei lettori. È pensabile per i quotidiani sviluppare un modello di business imperniato sul digitale e a pagamento? È difficile dirlo.

Il punto di vista dei lettori di Economia & Management

Presentiamo qui alcuni risultati di un sondaggio realizzato tra un piccolo campione di lettori di Economia & Management[19], il 92 per cento del quale è un lettore di quotidiani. Il 69 per cento lo legge su carta e in digitale, il 26 per cento solo in digitale e il 4 per cento solo su carta. Per il 43 per cento i due supporti si equivalgono, mentre il 21 per cento preferisce la carta e il 36 per cento il digitale. Focalizzando l’attenzione sul supporto digitale, il 52 per cento legge il quotidiano accedendo al sito web, il 26 per cento utilizzando l’applicazione, il 12 per cento lo legge attraverso i social media e l’8 per cento mediante la newsletter. Inoltre, la lettura avviene per il 37 per cento da computer, per il 32 per cento mediante tablet e per il 31 per cento utilizzando lo smartphone. I due quotidiani più letti dai lettori di Economia & Management sono Il Sole 24 Ore (letto dal 68 per cento) e il Corriere della Sera (letto dal 51 per cento). Seguono la Repubblica (36 per cento) e La Gazzetta dello Sport (15 per cento). Il 45 per cento legge anche quotidiani stranieri. I principali dei quali sono: Financial Times (29 per cento), The New York Times (20 per cento), The Guardian (17 per cento), Wall Street Journal (12 per cento). La lettura dei quotidiani occupa, per il 57 per cento dei partecipanti al sondaggio, tra mezz’ora e un’ora al giorno (tutti i giorni), per il 31 per cento meno di mezz’ora al giorno, per il 7 per cento più di un’ora al giorno e il 6 per cento non li legge tutti i giorni. Il 52 per cento ritiene i quotidiani il mezzo più affidabile per le notizie, seguono la radio (21 per cento), la televisione (11 per cento) e i social media (9 per cento). Il campione di Economia & Management, quindi, è un campione di lettori «onnivoro»: legge su carta e in digitale, su più supporti, legge più quotidiani (italiani e stranieri) e ritiene i quotidiani più affidabili degli altri media. Infine, il 63 per cento del campione cui è stato chiesto di ipotizzare il futuro dei quotidiani pensa che questi sopravvivranno come prodotti di nicchia.

Alla ricerca di un nuovo modello di business

Nel 2019, in un campione di 6 Paesi (Finlandia, Regno Unito, Francia, Germania, Italia, Polonia e Stati Uniti) la percentuale di quotidiani che ha adottato un modello a pagamento è pari al 69 per cento (per i quotidiani solo digitali questa percentuale scende al 6 per cento)[20]. Il prezzo medio dell’abbonamento mensile è pari a 14 euro. La percentuale di abbonati solo digitali a un quotidiano è stata pari al 15 per cento in Norvegia, al 14 per cento in Svezia, all’8 per cento negli Stati Uniti, al 6 per cento in Finlandia e Danimarca, al 4 per cento nel Regno Unito e al 3 per cento in Spagna e in Italia[21]. La decisione di acquistare un abbonamento per soddisfare il proprio fabbisogno di informazione utilizzando un supporto digitale riguarda, in genere, un solo quotidiano. Quest’ultimo dato deve essere confrontato con la propensione ad acquistare un abbonamento per soddisfare altri bisogni – come quello dell’intrattenimento – utilizzando altri media (per esempio, video e musica). A questo proposito, poste di fronte alla scelta di un solo abbonamento le persone con meno di 45 anni hanno così risposto: il 37 per cento sceglierebbe l’abbonamento a un servizio di video streaming, il 15 per cento di streaming musicale e il 7 per cento un servizio di informazione online. La percentuale per il servizio di informazione online sale al 15 per cento per le persone con più di 45 anni[22]. Questi dati, quindi, ci dicono che la propensione a pagare per il supporto digitale è relativamente bassa ed eterogenea rispetto ai differenti Paesi.

Gli effetti del paywall

Un altro aspetto da considerare riguarda la variabilità di questa propensione in funzione del tipo di quotidiano che si considera. Per esempio, in uno studio condotto per comprendere gli impatti legati al paywall[23] è stato dimostrato che la sua introduzione diminuisce il numero di pagine viste al giorno e che questa diminuzione è più bassa per i quotidiani che pubblicano contenuti (a) di carattere politico, economico-finanziario e sportivo, (b) unici (ossia, non pubblicati da altri quotidiani), (c) con un orientamento liberal. Questi risultati sono coerenti a quelli di un altro studio che ha dimostrato come il paywall incida negativamente sui lettori occasionali interessati a contenuti popolari e meno sui lettori assidui interessati a contenuti di nicchia[24]. I dati di questi studi ci dicono che il paywall è maggiormente sostenibile per i quotidiani di qualità e/o per quelli specializzati. Inoltre, il riferimento all’orientamento liberal è coerente con un altro risultato[25]: i cittadini con orientamento populista consumano più televisione rispetto ai cittadini non-populisti che, invece, consumano più radio e carta stampata. Inoltre, focalizzando l’attenzione sul supporto digitale, i primi utilizzano come principale porta di ingresso dell’informazione i social media rispetto ai secondi e condividono e commentano maggiormente contenuti informativi attraverso i social media.

Le differenze anagrafiche

C’è, inoltre, una grande differenza nell’utilizzo delle fonti di informazione in base all’età e alle generazioni. Questo utilizzo si differenzia in funzione del supporto/dispositivo utilizzato e del tipo di media preferito. Per la maggioranza relativa (45 per cento) dei cittadini con meno di 35 anni il primo contatto al mattino con l’informazione avviene attraverso lo smartphone, mentre per la maggioranza relativa (30 per cento) dei cittadini con 35 anni o più il primo contatto avviene attraverso la televisione. Inoltre, tra tutti coloro utilizzano lo smartphone per finalità legate all’informazione, gli under 35 lo fanno attraverso i social media o i sistemi di messaggistica, mentre i cittadini con 35 anni o più accedono direttamente al sito o all’applicazione di un quotidiano o di un altro prodotto informativo. Infine, la percentuale di coloro che, per accedere alle news, preferiscono il formato testo è pari al 58 per cento per i cittadini tra i 18 e i 24 anni, il 64 per cento per i cittadini tra i 25 e i 34 anni e il 70 per cento per i cittadini con 35 o più anni[26].

Una difficile convivenza

Torniamo ora, invece, ai quotidiani e alle scelte fatte. Il rapporto tra sfruttamento del supporto cartaceo ed esplorazione del supporto digitale è stato gestito con difficoltà. I quotidiani sono intervenuti più volte sugli organici (riducendo il numero di lavoratori poligrafici e di giornalisti, appoggiandosi, sempre più spesso, ai freelance e ai collaboratori esterni), sull’organizzazione del lavoro (prima separando e poi integrando chi si occupava del prodotto cartaceo e chi si occupava dei prodotti digitali), sullo sviluppo delle competenze digitali da affiancare a quelle più strettamente editoriali. Su questo fronte i quotidiani hanno iniziato a lavorare sui dati relativi alle preferenze e alle abitudini di utilizzo e consumo dei lettori, giungendo a modificare gli articoli in funzione delle reazioni dei propri lettori. Questo va nella direzione di una sempre maggiore personalizzazione del prodotto che va incontro alla frammentazione del pubblico. Però, basare l’attività editoriale sulle preferenze dei lettori rischia anche di depotenziare il ruolo dei quotidiani nel definire l’agenda e, quindi, il loro grado di influenza sociale e di unicità dei propri contenuti. Infine, per contenere i costi e/o per avere le risorse economico-finanziarie indispensabili per sviluppare i prodotti digitali, gli editori hanno indirizzato la propria attenzione verso le economie di scala mettendo in campo operazioni di esternalizzazione e/o acquisizione e fusione.

Per alcuni quotidiani questi cambiamenti sono stati più semplici. Per esempio, alcuni sono stati avvantaggiati dall’ampio bacino di lettori di cui già disponevano: si pensi al New York Times e al Guardian che si rivolgono a un’élite liberal nazionale e internazionale di lettori in lingua inglese (il 14 per cento dei ricavi del Guardian e il 16 per cento dei ricavi del New York Times sono realizzati all’estero), oppure Le Monde che si rivolge ai lettori francofoni. Tutti hanno investito molto sul digitale, ma con differenze in termini di prodotti sviluppati e offerte economiche. Il New York Times oltre ad aver adottato un paywall quantitativo e a voler essere un prodotto di qualità[27] ha anche sviluppato prodotti popolari come le parole crociate e le applicazioni dedicate alla cucina. Il Guardian ha deciso di non adottare il paywall, ma di sviluppare un modello di finanziamento basato sulla membership[28] e sull’abbonamento al sito e all’applicazione per avere contenuti senza pubblicità[29]. Le Monde, che ha il 57 per cento della propria diffusione pagata sul digitale e il 43 per cento sulla carta, diviso a sua volta tra il 29,1 per cento di abbonamenti cartacei e il 13,9 per cento di vendite di copie singole[30] ha deciso di ridurre il numero di articoli pubblicati e aumentare il numero di giornalisti per garantire maggior qualità[31]. A questi quotidiani, poi, non possono non essere aggiunte le due testate economico-finanziarie globali, ossia il Financial Times e il Wall Street Journal.

Alcuni possibili scenari futuri

Da quanto abbiamo scritto emerge come la crisi dei quotidiani non dipenda solo dall’ambiente esterno, ma anche da scelte compiute dagli editori che, in un certo senso, si sono scavati la fossa da soli. Questi hanno diversificato, imitato e posizionato i propri prodotti verso il basso, in questo modo non solo non sono riusciti ad allargare la base dei propri lettori, ma hanno messo in fuga parte di quelli che erano già loro clienti. Cosa dovrebbero fare, quindi, i quotidiani per cercare di gestire questa situazione? Alcune soluzioni potrebbero essere le seguenti:

- rivalutare la versione cartacea dato che, nella maggior parte dei casi, rappresenta il supporto da cui generano la maggior parte dei ricavi e che è caratterizzata da una percezione di valore superiore. Questo non significa mantenere lo status-quo, ma innovare il supporto, cambiando la distribuzione e la rete di vendita, rivendendo le scelte relative alla periodicità, lavorando maggiormente sull’integrazione/complementarietà con il digitale. Inoltre, la carta potrebbe essere rivalutata così come avvenuto per il vinile nel settore della musica;

- abbandonare la sudditanza nei confronti degli altri media (televisione e social media), sviluppando un prodotto unico e differente rispetto agli altri media;

- posizionare i propri prodotti verso l’alto, abbandonando la popolarizzazione avviata nel corso degli anni Novanta del secolo scorso;

- comprendere che è il lettore il principale finanziatore del prodotto e, quindi, sviluppare una logica commerciale che tenga conto del riequilibrio intervenuto tra mercato dei lettori e mercato pubblicitario.

Queste scelte ovviamente rendono il quotidiano non più un prodotto di massa, ma un prodotto di nicchia. Il quotidiano sarà quindi destinato a un’élite di lettori disposti a pagare per sentirsi parte di questo nucleo ristretto, garantendosi la possibilità di avere informazioni di qualità che gli altri non possono avere? Se la risposta a questa domanda sarà positiva ci saranno delle ripercussioni: da una parte, sul funzionamento dei sistemi democratici perché parte della popolazione sarà esclusa dall’informazione di qualità; dall’altra, sul settore editoriale perché non tutti potranno sopravvivere. Qui si apre anche un altro scenario, quello in cui i quotidiani non verrebbero più considerati beni di mercato e, quindi, gli editori si trasformerebbero in imprese no-profit basate sulla filantropia privata o sul finanziamento pubblico.

In sintesi

- Negli anni Novanta e nei primi anni Duemila, la maggioranza degli editori e dei quotidiani adottarono lo stesso modello di business della televisione commerciale: i contenuti pubblicati divennero fruibili a tutti a titolo gratuito e si decise che i ricavi digitali sarebbero derivati solo dalla raccolta pubblicitaria. In questo modo, l’informazione venne trasformata in una commodity, incidendo negativamente sulla propensione a pagare da parte dei lettori di giornali.

- A parte alcune eccellenze internazionali (New York Times, Le Monde, Guardian, Financial Times, Wall Street Journal), il rapporto tra sfruttamento del supporto cartaceo ed esplorazione del supporto digitale è stato gestito con difficoltà da quasi tutti gli editori.

- Tra i possibili sviluppi futuri del settore, emerge la possibilità di riposizionare il prodotto-quotidiano verso l’alto, abbandonando la «popolarizzazione» avviata nel corso degli anni Novanta del secolo scorso, e sviluppare una logica commerciale che tenga conto del riequilibrio intervenuto tra mercato dei lettori e mercato pubblicitario.

H.I. Chyi, S.C. Lewis, N. Zheng, «A Matter of life and death? Examining how newspapers covered the newspaper “crisis”», Journalism studies, 13(3), 2012, pp. 305-324; «A once unimaginable scenario: No more newspapers», The Washington Post, 21 marzo 2018; «New York Times CEO: Print journalism has maybe another 10 years», CNBC, 12 febbraio 2018; «NYT editor predicts almost all newspapers will die in 5 years», Fast Company, 21 maggio 2019.

P. Meyer, The Vanishing Newspaper: Saving Journalism in the Information Age, University of Missouri Press, 2009; M. Edge, «Are UK newspapers really dying? A financial analysis of newspaper publishing companies», Journal of media business studies, 16(1), 2019, pp. 19-39.

Public Policy Forum, The shattered mirror: news, democracy, and trust in the digital age, 2017.

B. I. Mierzejewska, D. Yim, P.M. Napoli, H. C. Lucas Jr., A. Al-Hasan, «Evaluating strategic approaches to competitive displacement: the case of the u.s. newspaper industry», Journal of media economics, 30(1), 2017, pp. 19-30.

P.M. Napoli, Evolutionary theories of media institutions and their responses to new technologies, in L. Lederman (a cura di), Communication theory: A reader, Kendall Hunt, Dubuque, 1998, pp. 315-329.

F. Perretti, G. Negro, «La carta e lo spazio digitale. “New York Times” e “Wall Street Journal”», Problemi dell’informazione, XXV(3), 2000, pp. 346-366.

P. Mancini, Il sistema fragile, Roma, Carocci, 2000.

P. Murialdi, La stampa italiana: alla liberazione ai giorni nostri, Bari, Laterza, 1995.

Si veda il contributo «Il trionfo della soggettività (e dello smartphone)» di De Rita presente su questo numero della rivista.

C. Draghi, «“Corriere” e “Repubblica”. Gli anni del sorpasso, la ripresa, il mielismo. Poi arriva De Bortoli e fa un “giornale moderno con l’anima antica”», Problemi dell’informazione, 1, 2001, pp. 41-50; L. Fortunati, J. O’Sullivan, «Unsung convergence of analogue to analogue: Add-ons supplements and the evolving roles of the print newspaper», European Journal of Communication, 34(5), 2019, pp. 473-487.

«Anni 80, l’epoca d’oro per i giornali in Italia», Reset.it, 21 maggio 2013.

Nel 1991 il presidente della Fieg dichiarava: «La televisione minaccia di travolgere la carta stampata e di relegarla in una posizione marginale», in P. Murialdi, La stampa italiana: alla liberazione ai giorni nostri, Bari, Laterza, 1995, p. 253.

J.G. March, «Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning», Organization science, 2(1), 1991, pp. 71-87.

H.I. Chyi, S.C. Lewis, N. Zheng, «A Matter of life and death? Examining how newspapers covered the newspaper “crisis”», cit.; H.I. Chyi, O. Tenenboim, «From analog dollars to digital dimes: a look into the performance of us newspapers», Journalism practice, 13(8), 2019, pp. 988-992; H.I. Chyi, O. Tenenboim, «Charging more and wondering why readership declined? A longitudinal study of U.S. newspapers’ price hikes, 2008-2016», Journalism studies, 20(14), pp. 2113-2129.

AGCOM, Relazione annuale 2019.

Relativamente al supporto distinguiamo tra: carta e tutto ciò che è analogico e digitale. Relativamente ai clienti distinguiamo tra: lettori o altre fonti che non siano la pubblicità.

I dati sono frutto di elaborazioni basate sui seguenti documenti: per RCS Media Group, il «Resoconto intermedio di gestione al 30 settembre 2019»; per GEDI, la «Relazione finanziaria annuale al 31 dicembre 2018»; per il Guardian Media Group, l’«Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements»; per la The New York Times Company, il 2001, 2010, 2014 e 2019 «Annual Report» e la «Q4 2019 Earnings Release».

H.I. Chyi, O. Tenenboim, «Charging more and wondering why readership declined? A longitudinal study of U.S. newspapers’ price hikes, 2008-2016», cit.

Si tratta di un campione di 97 rispondenti. L’età media è pari a 47 anni (il 54 per cento ha più di 45 anni), il 60 per cento sono quadri, dirigenti o liberi professionisti, il 77 per cento ha un elevato livello di istruzione (laurea o master/dottorato), il 70 per cento sono uomini e il 30 per cento donne. Il questionario è stato inviato via posta elettronica nel gennaio 2020.

Reuters Institute, Pay Models for Online News in the US and Europe: 2019 Update, 2019.

Reuters Institute, Digital News Report 2019: http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/.

Ibidem.

H. Kim, R. Song, Y. Kim, «Newspapers’ content policy and the effect of paywalls on pageviews», Journal of interactive marketing, 49, 2020, pp. 54-69.

H. Oh, A. Animesh, A. Pinsonneault, «Free versus for-a-fee: the impact of a paywall on the pattern and effectiveness of word-of-mouth via social media», MIS Quarterly, 40(1), 2016, pp. 31-56.

Reuters Institute, Digital News Report 2019, cit.

Ibidem.

«We bring trusted expertise to every story. Triple-checking sources. Vetting leads. Upholding the code of ethics. It takes all these investigative skills and more for our newsroom to uncover the facts», «Welcome to The New York Times coverage that brings you closer», The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/subscription/why?campaignId=6WYWY.

«Your support helps protect the Guardian’s independence and it means we can keep delivering quality journalism that’s open for everyone around the world. Every contribution, however big or small, is so valuable for our future», «Support our journalism in Europe and beyond», The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/international.

«Read The Guardian’s quality, independent journalism without interruptions. Enjoy an ad-free experience across all of your devices when you’re signed in on your apps and theguardian.com» Ibidem.

L’ACPM, l’alliance pour les chiffres de la presse et des médias, https://www.acpm.fr.

«Entre 2018 et 2019, Le Monde a réduit de 14 pour cent le nombre total d’articles publiés (-25 pour cent en 2 ans). Plus de journalistes (près de 500 désormais), plus de temps pour enquêter. Résultat ? L’audience web a fortement progressé (+11 pour cent) comme la diffusion (print et web) du journal (+11 pour cent).» («Tra il 2018 e il 2019, Le Monde ha ridotto il numero totale di articoli pubblicati del 14 per cento (-25 per cento in 2 anni). Più giornalisti (ora quasi 500), più tempo per indagare. Il risultato? Il pubblico del web è cresciuto fortemente (+11 per cento) così come la diffusione (su stampa e web) del giornale (+11 per cento)», TdR), «Moins d’articles, plus de journalistes et plus d’audience : la formule gagnante du journal Le Monde», L’ADN, 20 gennaio 2020.