E&M

2021/4

Gender Pay Gap: The Role of Businesses

Over the course of the last 30 years, gender pay differences in the private sector in Italy have fallen considerably, although they remain very noticeable among high incomes: the difference between men and women is 30 percent, in favor of the former. In 2021, the birth of a child still represents one of the main factors that contributes to accentuating the gender employment and pay gaps. In Italy, the child penalty – the percentage loss of income that mothers suffer following a pregnancy – is among the highest in Europe. On the other hand, approximately 30 percent of the pay gap depends on the compensation policies that businesses adopt for men and women. In this regard, in March 2021 the European Commission presented a proposal for a directive on pay transparency, to ensure that women receive equal compensation for their work.

The gender gaps in pay and employment represent a strong obstacle to reaching actual parity between men and women in the labor market in Europe and Italy. Despite the numerous analyses that demonstrate the important positive effects of female empowerment on economic outcomes – at both the macroeconomic level and that of individual companies[1] – significant differences remain and the measures adopted to overcome them are often timid, and concentrated in just a few countries or virtuous companies.

At the end of 2020, Italy had one of the worst rates of female employment in the European Union (48.6 percent), better only than Greece and a full 14 points below the European average. According to Eurostat data, the gap between male and female hourly pay is 14.1 percent in the European Union, and 4.7 in Italy, with enormous differences between the public and private sector, where the gap is equal to 3.8 percent and 17 percent, respectively.[2]

The reduction of the gender pay gap thus involves the private sector and the dynamics of compensation within companies.

In this article I will present some data on the dynamics and the level of the gender pay gap in the private sector in Italy; I will discuss the principal causes of gender pay gaps, focusing in particular on those that more directly involve the role of businesses; and lastly, I will analyze pay transparency as a lever for the reduction of pay gaps.

The gender pay gap in Italy

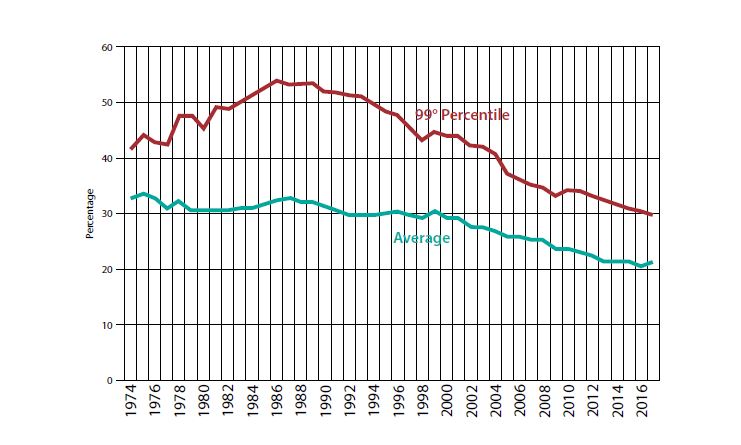

Gender pay gaps in the private sector have decreased considerably over time, indicating that some progress has been made in this area. Using INPS data on the universe of Italian private sector workers, made available thanks to the VisitInps search program, it is possible to demonstrate that, starting in the 1970s, the average gender gap in gross annual pay for full-time workers fell from 33 percent in 1974 to 21 percent in 2017. The convergence between male and female pay took place at different speeds in different periods. Figure 1 shows that, looking at the average (the dotted line), is was rather slow until the end of the 1990s, to then accelerate starting in the 2000s, and then stop again in recent years.

If we focus on the average, we look at the portion of the distribution of income from work that includes the richest one percent of workers, we notice that for the entire period considered that value is well above the average, offering evidence for the phenomenon of the "glass ceiling": the pay differences between men and women are more accentuated among higher employment incomes than among average incomes. While in 2017 women earned on average 20 percent less than men, among workers with higher salaries the difference rose to 30 percent. However, with respect to the gap at the average, the gap at the top showed a rather rapid reduction starting from the middle of the 1980s, going from a maximum value of 54 percent in 1986 to a minimum of 30 percent in 2017. In the highest percentile, the weekly pay for a man in this portion of the pay distribution oscillates between 2,000 and 10,000 euros. To the contrary, a woman in the same portion of the female distribution earns between approximately 1,200 and 4,800 euros.[3] The goal of reducing the pay gap can thus not ignore an understanding of what happens to male and female worker in the most lucrative segments of the labor market.

Figure 1 Gender pay gap at the average and at the 99th percentile, 1974-2017 (Italy)

Source: Elaboration of INPS data. A. Casarico, S. Lattanzio, "Differenziali salariali di genere e ruolo delle imprese," in Il Bilancio di genere per l'esercizio finanziario 2017, Ministry of Economics and Finance (2018).

Maternity and businesses

While the data indicates that the pay gap between men and women in the private sector is high and persistent over time – with a noticeable variety depending on the portion of pay distribution – it is natural to ask what the mechanisms are that determine the opening and persistence of this gap. Historically, the pay gap has been attributed to differences in education between men and women.[4] However, today women reach levels of education that are equal – if not higher – than those of men. The convergence of education rates has in fact been one of the factors that has driven the convergence between male and female pay over the years.[5] The same cannot be said for the impact of maternity.

The child penalty

In 2021, the birth of a child still represents a turning point in women's employment careers, and is still one of the main factors that contributes to the presence of gender employment and pay gaps. The labor market cost of the birth of a child is commonly called the child penalty. This measures the loss of employment income that mothers suffer following pregnancy, if compared with fathers or with women who have the same age, skills and pay characteristics, but don't have children. In Scandinavian countries as well, that usually lead international gender parity rankings, mothers pay a long-term penalty of over 20 percent in terms of lower employment income compared to fathers after the birth of a child. In Austria, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States and Spain – other countries in which that penalty has been measured – the loss is even greater. Italy is no exception. We obtained an estimate of the long-term child penalty for our country based on a same of INPS data on subordinate employees in the private sector between 1985 and 2018.[6] Fifteen years after the birth of a child, the annual salaries of mothers have grown 57 percent less than those of women without children. The drop is very strong right after the birth, but the gap created remains.

Why does the income of workers "change paths" after maternity? Fifteen years after the birth of a child, over two-thirds of the child penalty (68 percent) can be explained by a reduction of labor supply of mothers compared to non-mothers, since the former work fewer weeks in a year. Twenty percent is due to a shift to part-time employment, while 12 percent can be traced to lower full-time equivalent weekly pay. So it is the reduction of mothers' labor supply that contributes the most to the penalty in annual pay.

The "penalty" in employment income linked to the birth of a child encompasses multiple aspects. It can reflect the preferences of mothers, who wish to spend time with their children and thus reduce the time dedicated to work; it can indicate the difficulty of reconciling work and family, that the absence of care services and pre-schools, or the lack of sharing within the family, can make insurmountable; it can regard stereotypes and social norms that see mothers as mainly or exclusively responsible for child care; and lastly, it can depend on the characteristics of the companies in which the mothers work.

On this last point, our analysis offers no evidence that the entity of the penalty depends on the dimensions of the company in which mothers work, but indicate that it is higher in companies that pay lower average salaries or in companies with a higher percentage of women employed. The first result could reflect the fact that companies that offer lower pay are companies that also guarantee few non-pecuniary benefits for women, like company pre-schools, flexible work hours, or the possibility to work from home. It could also be that women are concentrated in companies with these characteristics because they have fewer job offers, stricter time constraints in searching for work, or greater mobility costs. The fact that the pay penalty is greater in companies with a higher share of women employed could at first glance seem counterintuitive, given that a high concentration of women could indicate that the company is particularly woman-friendly. In reality, there are various studies that demonstrate that women are not only concentrated in particular sectors in which compensation is lower on average, but also in companies that pay all of their workers lower in general.

Pay gaps and the role of businesses

The growing availability of administrative data that allows for associating each worker with the characteristics of the company they work for has made it possible to develop analyses aimed at quantifying the impact of companies' wage policies on pay inequality in general, and on gender inequality in particular.[7] The compensation policies or career paths adopted, the organization of work times, the presence or absence of complementary services to work (company pre-school, for example) distinguish each company (technically, they are captured by the "fixed effects" of a business) and can contribute to gender pay inequality. Using INPS data on the universe of workers in the private sector in Italy, we find that 30 percent of the gender pay gap depends on the compensation policies that businesses adopt for men and women.[8] It is possible to further break down the contribution of businesses to identify two different mechanisms that can generate it: on the one hand, women could be concentrated in companies that pay lower pay to both genders (sorting: inequality among companies); on the other, despite working in the same companies, female workers could have less contractual power than men and not be able to negotiate the same pay or the same career paths, thus producing a growth in overall inequality due to factors internal to single companies (inequality within the company). Our analysis reveals that the effects of sorting are quantitatively more important in explaining the contribution of companies to average pay inequality, while phenomena of vertical segregation within companies are more relevant – as can be expected intuitively – for male and female workers who are in the higher percentiles of employment income distribution.

It is important to stress that the distribution of male and female workers in the hierarchy of a company is a crucial element in the increase of gender inequality. If the goal in a company is to favor pay equality, it will not be sufficient to ensure that men and women receive the same compensation for the same kind of work, but also to consider how many men and women have the same career opportunities and are distributed in a balanced manner among the various degrees of responsibility within the company.

Pay transparency

In line with its "Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025," in March 2021 the European Commission presented a proposal for a directive on pay transparency, to ensure that women receive equal compensation for their work.[9] The proposal is based on a process already started some time ago by the European institutions, with the goal of pushing national parliaments to increase the fight against gender inequality in the labor market. The Directive has three goals: to establish pay transparency measures that can help women and men searching for a job; to strengthen the right of workers to know the income level of colleagues who perform the same duties; and to introduce the obligation to disclose data on the gender pay gap for companies with more than 250 employees. In particular, strengthening the reporting obligations has the goal of providing an incentive for a virtuous process, that leads companies to develop greater awareness regarding their employment and pay structure from a gender standpoint, and at the same time help highlight any forms of discrimination.

There is no dearth of international examples of business reporting:[10] the United Kingdom, Denmark, Switzerland, France, and Austria are some of the countries that require companies to draw up reports and communicate statistics on male and female personnel and their compensation.

In the United Kingdom and France, companies with more than 250 employees are required to publish annual data on the gender pay gap, while in Denmark and Switzerland the threshold is set at 35 and 50 employees, respectively. In Austria, the decision has been to gradually expand the number of companies involved, starting with the largest ones. In the United Kingdom, companies are required to provide information on the average and median gap in pay and bonuses and the distribution of male and female workers in terms of pay quartiles. There is a portal dedicated to gender pay gap reporting, that can be consulted by whomever is interested. It is also possible to see the list of companies that have not complied with the reporting obligations and what actions have been adopted in the case of breach of the law. The lever of transparency – a sort of "black list" (name and shame) – is thus used as an incentive for companies to respect the law and properly provide data, even though some have doubts of the true effectiveness of this system, without explicit sanctions. Some studies on data from the United Kingdom show that the policy of transparency has caused a reduction of the gender pay gap in companies affected by the obligations compared to those that are not,[11] in addition to having pushed the former to publish job listings that are more careful in terms of gender language or that have greater opportunities for flexibility.[12] In Austria and Belgium, on the other hand, confidentiality is maintained regarding the relationships, which limits the reputational costs (or benefits) of gender gaps in companies.

In Italy, the Equal Opportunity Code (Legislative Decree 198 of 2006) requires companies with more than 100 employees to draw up a report at least every two years on the situation of male and female personnel in terms of employment and compensation, while Legislative Decree 254 of 2016 on non-financial reporting requires companies with at least 500 employees to indicate the results relating to non-financial aspects, including measures to achieve gender parity. Various proposals have been submitted in the Italian Parliament to amend the Equal Opportunity Code to make the disclosure obligations for companies regarding data on compensation and distribution of male and female workers more binding, and the debate is still underway.[13]

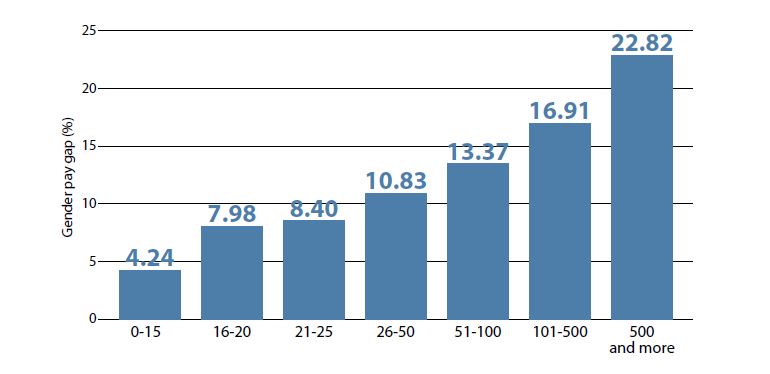

Promoting transparency in business data can lead to benefits in the path towards actual gender parity. Although legislation is an important lever to incentivize communication of data, companies themselves can systematically monitor labor force indicators that separate by gender, to assess if and what diversity goals have been acquired. Monitoring not only aggregate statistics (such as the average gender pay gap), but also data on the presence of women and men in various portions of income distribution within the company itself, can for example help identify phenomena of vertical segregation. It is easier for this to occur in large-sized companies, because it is there that the gender pay gap tends to increase: based on a sample of INPS data referring to the private sector, the average gender pay gap is less than 5 percent in companies with fewer than 15 employees and equal to 23 percent in those with more than 500 employees, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Gender pay gap by company size

*Note: gender pay gap calculated as percentage difference in average daily pay of men and women.

Source: A. Casarico, Informal Hearing at Labor Commission of the Chamber of Deputies on the subject of equal opportunity, January 30, 2020. Elaboration on a sample of INPS data for the private sector.

The debate over the increase of transparency of work force data and worker compensation is accompanied by the question of whether there can be undesired effects for the goal of parity. Some stress that companies could hire fewer women in non-management positions, making use of outsourcing, only in order to improve their numbers; others say that the gender pay gap could temporarily worsen because more women would be hired in junior management positions, which per se would not be a negative outcome.

It is in any event undeniable that an evaluation of pay policies and career paths by gender in the business world is a significant element to tackle the gender gap in the labor market. In the framework designed by the European Commission, businesses can begin to strengthen this process.

Synopsis

- Over the course of the last 30 years, gender pay differences in the private sector in Italy have fallen considerably, although they remain very noticeable among high incomes: the difference between men and women is 30 percent, in favor of the former.

- In 2021, the birth of a child still represents one of the main factors that contributes to accentuating the gender employment and pay gaps. In Italy, the child penalty – the percentage loss of income that mothers suffer following a pregnancy – is among the highest in Europe.

- Approximately 30 percent of the pay gap depends on the compensation policies that businesses adopt for men and women. In this regard, in March 2021 the European Commission presented a proposal for a directive on pay transparency, to ensure that women receive equal compensation for their work.

"Economic Case for Gender Equality in the EU", EIGE, 2021.

"Gender Pay Gap Statistics", Eurostat, 2021.

A. Casarico, S. Lattanzio, "L’andamento dei top earners nel caso dei lavoratori dipendenti," INPS Annual Report, Part III, 2019, pp. 128-133.

J.G. Altonji, R.M. Blank, "Race and Gender in the Labor Market," in O. Ashenfelter, D. Card (editors), Handbook of Labor Economics, 3, Amsterdam, Elsevier, 1999, pp. 3143-3259.

For a discussion of the role of the fields of study with a lower concentration of young women in STEM disciplines, see M. Bertrand, "Gender in the 21st Century," American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 110(5), 2020, pp. 1-24.

For the details of the methodology, see A. Casarico, S. Lattanzio, "Behind the Child Penalty: Understanding what Contributes to the Labour Market Costs of Motherhood," CESIfo working paper 9155, June 2021.

D. Card, A.R. Cardoso, P. Kline, "Bargaining, Sorting, and the Gender Wage Gap: Quantifying the Impact of Firms on the Relative Pay of Women," Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(2), 2016, pp. 633-686; A. Casarico, S. Lattanzio, "What Firms Do: Gender Inequality in Llinked Employer-Employee Data, WorkINPS paper n. 24 and Cambridge-INET working paper 1915, 2019; E. Coudin, S. Maillard, M. To, "Family, Firms and the Gender Wage Gap in France," IFS Working Papers W18/01, Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2018; B. Bruns, "Changes in Workplace Heterogeneity and How They Widen the Gender Wage Gap," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 11(2), 2019, pp. 74-113.

Casarico, Lattanzio, 2019, op. cit.

"Proposal for a directive of the European parliament and of the council to strengthen the application of the principle of equal pay for equal work or work of equal value between men and women through pay transparency and enforcement mechanisms", European Commission, March 4, 2021.

"Pay Transparency in Europe: First Experiences with Gender Pay Report and Audits in four Member States", Eurofound, 2018.

J. Blundell, "Wage Responses to Gender Pay Gap Reporting Requirements," 2020.

E. Duchini, S. Simion, A. Turrell, "Pay Transparency and Cracks in the Glass Ceiling," CAGE working paper 48, 2020.

"Divari di genere: la trasparenza aiuta a limitarli?" lavoce.info, February 7, 2020.