E&M

2019/3

Career Progression in Italy: Old Paths, New Tensions

Over the last decade, the world economy has lived through big transformations, that have had repercussions on businesses with phenomena such as outsourcing, downsizing, and organizational flattening, to name a few. Working relationships have become less long-lasting, with a steady increase in temporary contracts, supported also by digital platforms. These transformations have had a significant impact on individuals’ careers, inside and outside companies.

Nonetheless, Italy shows limited incidence of high-mobility career paths. Institutional factors, such as the rigidity of the labor market, and cultural factors, e.g. a low orientation to geographical mobility, contribute to explaining the results achieved with consequences for remuneration that on average is lower than that of other Western countries, a fact confirmed by the existing gap between perceived importance and achievement of economic success.

In a scenario of major changes, the role of companies remains important for individual development, although it does not seem to fill in the “well-known” gaps between the sexes as regards promotion and economic reward.

Over the last decade, the world economy has lived through big transformations, that have had repercussions on businesses with phenomena such as outsourcing, downsizing, and organizational flattening, to name a few[1]. These and other changes have had an impact on the nature of work itself, on the psychological relationship between individuals and employers, and on the way to conduct and conceive a career. Work dematerializes, leaving room first to the services and sectors with high knowledge intensity, and then to so-called Industry 4.0.[2] Working relationships have become less long-lasting, with a steady increase in temporary contracts, supported also by digital platforms, as in the so-called gig economy, a sector that is difficult to quantify but certainly growing in Italy as well.[3] These transformations have had a significant impact on individuals’ careers, inside and outside companies; in this article we will outline the theoretical facets of these repercussions, with an empirical focus on Italy.

Careers and Success: The Main Changes

The Career Is Dead - Long Live the Career. So reads the title of the book that Tim Hall, one of the most influential researchers on the subject, published in 1996. In the same year, another seminal text came out, by Michael Arthur and Denise Rousseau: The Boundaryless Career, where the traditionally understood boundaries were those of the enterprise. What had happened in companies and what phenomenon were the researchers recording? The continuous restructuring and reductions of staff, underway for many decades but particularly severe from the 1990s on, had undermined the idea of a lasting relationship with one or a few companies, founded on loyalty and commitment, in favor of the development of idiosyncratic relationships, based on the market.[4] It is in this context that the researchers theorize the idea of a career that goes beyond the boundaries of a single organization and is more changeable, like the faces of Proteus.[5] A career that develops among a number of companies, occupations, sectors, and professions and which today, more than twenty years later, also becomes autonomous and disconnected from traditional workplaces.

Although empirically the concept of a boundaryless career has been questioned,[6] and it now seems clear that it involves only a minority of the workforce, and the same can be said of the gig economy, the same changes that have led to the theorization of these models have also led to a rethinking of what is meant by “career success.” The latter was conceived and measured only objectively for a long time, mainly in terms of salaries and promotions. As early as the end of the 1980s, however, subjective component began to be recognized, relating to satisfaction with respect to the career in general, independent of extrinsic and quantifiable acknowledgements. This concept has subsequently been interpreted as multidimensional, that is, by measuring career satisfaction in relation to different aspects of professional development, for example the possibility of learning and challenges derived from the performance of the job or the quality of relations with colleagues.[7] However, credit must go to the international research group 5C (Cross-Cultural Collaboration on Contemporary Careers) for the development of a multidimensional scale of subjective career success, that has been validated worldwide. The group develops its research in the belief that cultural and institutional diversities accompany different interpretations of success and that not all dimensions have the same value in all countries. The seven dimensions of the scale, indicated below, have been developed on the basis of what people consider important in the definition of success:[8]

- learning and development – learning to be innovative in one’s work;

- financial security – receiving remuneration enabling a person to satisfy his and his family’s basic needs;

- financial success – achieving economic well-being and increasing one’s income;

- entrepreneurship – succeeding in an autonomous professional project;

- work-life balance – achieving a good balance between private life and work;

- positive work relationships – experiencing good work relationships and being appreciated by one’s colleagues;

- positive impact – contributing to the development of others and society.

In the 5c.careers site, the reader can find maps setting out the distribution of these dimensions in the different countries taking part in the study. The research is based on a sample of about 20,000 respondents from 31 countries.

The first empirical studies based on data gathered by the 5C research highlight the importance of the institutional and cultural context for careers, an aspect theorized years earlier by researchers in this field.[9] An initial project tested the effect of proactivity on two dimensions of subjective success: financial success and work-life balance.[10] Proactive actions include, among other things, the planning of one’s own path, the development of skills, and consultation with the most senior managers. The study stressed that proactive management of one’s career positively influences financial success and that this relationship is amplified by the cultural context.

A second project tested the way individuals manage various dimensions of subjective career success, bringing to light how differences in the institutional context influence the division and convergence of these associations.[11] Other studies, to be published soon, concentrate on specific aspects, such as the effect of career development activities on the perception of employability[12] or again the relationship between such activities and objective and subjective success.[13]

These studies contribute to the initial structuring of an international field of research into careers that takes its place alongside the already consolidated field of international human resource management,[14] and give a quick overview of the frontier topics in studies of careers. Below we present a focus on Italy based on the data of the study.

Careers in Italy

The gathering of Italian data for the 5C research project took place from 2014 to 2015 by the administration of an online questionnaire to a sample of workers with at least two years’ experience, divided by professional position (managers, professionals, clerical and service workers, skilled workers), sex, and age group, according to criteria that permitted comparability of results between the different countries taking part in the study.

Below we present the results of the respondents with an employment contract. This involves 606 people, 52.6 percent men, with an average age of 38.8 years (ranging from a minimum of 19 to a maximum of 66 years of age) and an average corporate seniority of 16.1 years. The sample represents the generational variety on the labor market today, with 22.3 percent belonging to the Baby Boomer generation (born before 1964), 37.8 percent to the Generation X (born between 1965 and 1980), and 39.9 percent to the Millennials or Generation Y (born after 1980). With reference to family condition, 57.3 percent are married or live with a partner and 47.7 percent have one or more children. In 18.3 percent of cases the partner does not work. Finally, with percentages far above the Italian average, 40.7 percent are university graduates and 6 percent have a doctorate: the proportion of respondents with higher education degrees is greater among those belonging to Generation X (52.6 percent), followed by the Millennials (44.8 percent), and the Baby Boomers (39.9 percent).

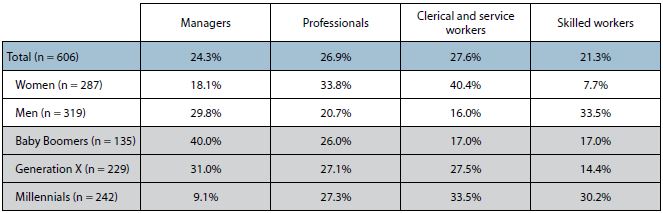

With reference to the professional profile of respondents, 24.3 percent work in managerial positions, 26.9 percent are professionals (e.g. engineers, lawyers, chemists, physicians), 27.6 percent work in offices or services (as shop assistants, secretaries, bartenders), and finally, 21.3% work in specialized roles that do not require a degree (for example, skilled manual workers, experts in technical or handicraft activities). Seniority in the job is 8.2 years on average.

Breaking down the professional profiles by gender, we note that women are prevalently occupied in office positions and as professionals, while men are concentrated in managerial positions and among skilled workers. From an analogous breakdown by generation, it emerges that the majority of the Baby Boomers and those belonging to Generation X are in managerial positions today, while Millennials work prevalently in office and skilled positions (Table 1).

Table 1 Distribution of the sample by professional profile

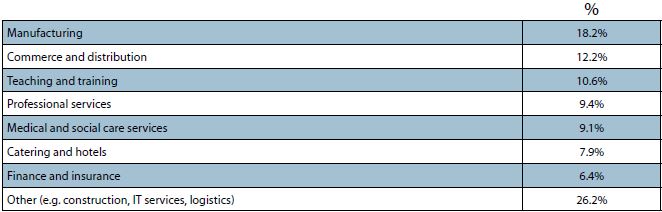

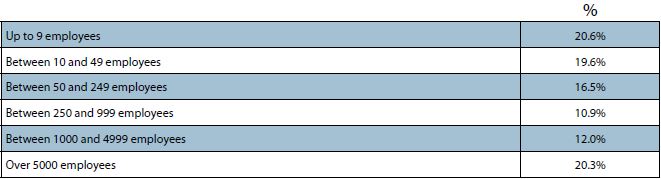

Regarding the types of organizations the respondents work in, most are in private companies (66.8 percent). Among these, the majority are Italian companies operating on a national (56.3%) and international level (24.9 percent). The distribution of the sample by industry and company size is illustrated in Tables 2 and 3. Corporate seniority is 9.9 years on average.

Table 2 Distribution of the sample by sector of employment

Table 3 Distribution of sample by company size

The questionnaire investigated some of the main attitudes to work, to understand the level of motivation of the respondents in carrying out their activity and towards their company. In general terms, a picture emerges of employees highly involved in their work (average engagement of 4.2 on a scale from 1 to 6) and, although to a lesser degree, with significant links to their companies (average corporate commitment 4.5 on a scale from 1 to 7). They do not seem interested in seeking a new job (the intention of leaving the company is 2.9 on a scale from 1 to 7), perhaps because they are not absolutely certain that they would find another job in a short time (the perception of employability is 3.8 on a scale of 1 to 7).

But what are the main characteristics of the career paths of the Italian workers who took part in the research?

First of all, the respondents show fairly “stable” career paths: 49.3 percent have worked in one or two companies during their careers, mainly in one or two industries (72.8 percent). In spite of an extreme variety of situations, the average values indicate fairly modest rates of change (on average 2.9 companies and 1.9 sectors), which increase with the level of responsibility achieved: average mobility for managers is 3.4 companies and 2.2 sectors in the course of their careers. On average, respondents change company every 7.7 years, with a slight difference between managers (8.2 years), professionals (8.5 years), clerical and service workers (6.9 years) and skilled workers (7.1 years). Lastly, with reference to mobility, it should be noted that mobility is also fairly limited geographically: 63 percent of respondents have never worked abroad and do not travel for their jobs.

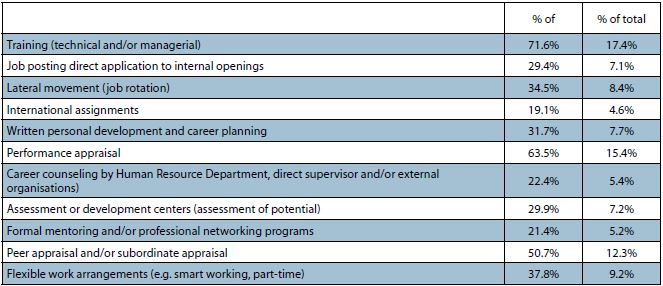

Moving on to illustrate career development activities (Table 4), it emerges from the questionnaires that the most common activity is training (71.6 percent of respondents state that they have attended at least one training course during their careers), followed by performance appraisal activities (63.5 percent) or peer evaluation (50.6 percent). More specific instruments of development are still not applied freely in companies, or are limited only to specific segments of collaborators: international assignments (19.1 percent), mentoring and networking programs (21.4 percent), and career counseling (22.4 percent). If we break down these activities according to respondents’ occupations, we see how international assignments have been experienced principally by the managers (47.7 percent). The same can be said of mentoring (37.7 percent) and career counseling programs (38.2 percent). In positions of less responsibility, the more common activities are training courses, various forms of assessment, and modes of flexible work arrangements to favor a balance between private and working life (e.g. flexible hours, part-time).

Table 4 Distribution of the sample by career support activities*

Note: *multiple answers could be given (n=2497).

We conclude by illustrating the principal indicators of objective and subjective career success of the Italian sample.

With reference to objective success, information was collected as to gross annual salary (in classes), the number of promotions received and the hierarchical level held. Almost half the sample (46.9 percent) state that they receive a gross annual salary of less than 25,000 euros, and another 26.1 percent are paid between 25,000 and 40,000 euros. Significant in this connection are the differences between the sexes: while 63.6 percent of men earn less than 40,000 euros, this percentage rises by 20 points (83.2 percent) among women. The presence of a gender gap in Italian women’s careers also emerges with reference to the number of promotions obtained; on average there are 2.3 promotions, while the figure falls to 1.95 for women and rises to 2.66 for men. Less marked, although present, is the difference with reference to the hierarchical level: while women – on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 represents the maximum level (e.g. CEO) and 10 the lowest entry level in the hierarchy – are positioned at an average level of 5.48, men are slightly higher up (5.05), with an overall sample average of 5.2.

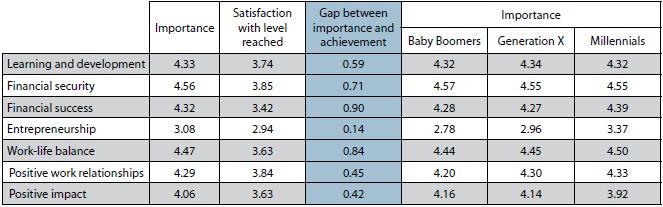

With reference to the seven dimensions of subjective success described earlier, the research investigated how important people consider these to be (on an increasing scale from 1 to 5) and whether they have reached a level at which they feel satisfied (on an increasing scale from 1 to 5) (Table 5). Financial security represents the most important aspect for respondents (4.56), followed by work-life balance (4.47), and learning (4.33). Financial security (3.85) and learning (3.74) are also two of the dimensions with which the workers feel most satisfied for the level reached, to which positive work relationships are added (3.84). The breakdown by generation shows greater attention to work-life balance and positive work relationships among the youngest, but also strong ambition both for financial success and for entrepreneurship. Overall, satisfaction for their own success in their career is on average 4.6 (on an increasing scale from 1 to 7).

Table 5 Dimensions of subjective success: importance and achievement

So…

The 5C research data for Italy show a still limited incidence of high-mobility career paths, in line with other empirical studies on the subject. Institutional factors, such as the rigidity of the labor market, and cultural factors, e.g. a low orientation to geographical mobility, contribute to explaining the results achieved with consequences for remuneration that on average is lower than that of other Western countries, a fact confirmed by the existing gap between perceived importance and achievement of economic success.

In a scenario of major changes, the role of companies remains important for individual development, although it does not seem to fill in the “well-known” gaps between the sexes as regards promotion and economic reward.

In brief

Italian workers have rather “stable and local” career paths. Almost half the sample analyzed in the study have lived their careers at one or at most two companies, changing jobs every 7.7 years. Geographical mobility is also limited: two out of three workers have never worked abroad and do not travel in their jobs.

Workers’ career development is prevalently supported by companies through training activity as well as performance appraisal activities. More sophisticated instruments of development such as international assignments, mentoring programs, and career counseling are reserved only to specific segments of employees.

What do people seek in their jobs? Among the indicators of success, the ones considered most important are financial security, work-life balance, and possibilities of learning. Millennials also pay close attention to relationships in the workplace. Precisely on the economic dimension, however, a number of problems emerge: remuneration is low on average compared with other Western countries (73 percent earn 40,000 euros or less), with significant gaps between the sexes.

The authors have contributed equally to the writing of this article.

S.R. Barley, B.A. Bechky, F.J. Milliken, “The changing nature of work: Careers, identities, and work lives in the 21st century,” Academy of Management Discoveries, 3(2), 2017, pp. 111-115.

M. De Paola, “Fare i conti con la gig economy,” Lavoce.info, 31/8/2018, available online: www.lavoce.info/archives/54741/54741/.

D.M. Rousseau, Psychological Contracts in Organizations. Understanding Written and Unwritten Agreements, Sage, Thousand Oaks (Ca), Sage, 1995.

J.P. Briscoe, D.T. Hall, “The interplay of boundaryless and protean careers: Combinations and implications,” Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(1), 2006, pp. 4-18.

S. Bagdadli et al., “The emergence of career boundaries in unbounded industries: Career odysseys in the Italian New Economy,” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(5), 2003, pp. 788-808; R.A. Rodrigues, D. Guest, “Have careers become boundaryless?,” Human Relations, 63(8), 2010, pp. 1157-1175.

K.M. Shockley et al., “Development of a new scale to measure subjective career success: A mixed?methods study,” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(1), 2016, pp. 128-153.

W. Mayrhofer et al., “Career success across the globe,” Organizational Dynamics, 45(3), 2016, pp. 197-205.

W. Mayrhofer, M. Meyer, J. Steyrer, “Contextual issues in the study of careers,” in H. Gunz, M. Peiperl (eds.), Handbook of career studies, Thousand Oaks (Ca), Sage, 2007, pp. 215-240; Y. Shen et al., “Career success across 11 countries: Implications for International Human Resource Management,” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(13), 2015, pp. 1753-1778.

A. Smale et al., “Proactive career behaviors and subjective career success: The effects of perceived organizational support and national culture,” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(1), 2019, pp. 105-122.

R. Kaše et al., “Career success schemas and their contextual embeddedness: A comparative configurational perspective,” Human Resource Management Journal, 2018, DOI:10.1111/1748-8583.12218.

S. Dello Russo et al., The Moderating Role of OCM and Labour Markets in the Relationship Between Age and Perceived Employability, paper presented at the 78th AOM Annual Meeting “Improving Lives,” Chicago (IL), 10-14.8.2018.

S. Bagdadli et al., Sponsored Mobility in Context: The Impact of Organizational Career Management on Objective Career Success and the Moderating Role of Institutional Factors, paper presented at the 78th AOM Annual Meeting “Improving Lives,” Chicago (IL), 10-14.8.2018; S. Bagdadli, M. Gianecchini, “Organizational Career Management practices and objective career success: A systematic review and framework,” Human Resource Management Review, 29(3), 2019, pp. 353-370.

C. Brewster et al., International Human Resource Management, London, Kogan Page Publishers, 2016.