E&M

2019/3

The Good and the Bad of the Gig Economy

Technological innovation is producing epochal transformations in the economy, not only making heretofore unthinkable organizational scenarios possible, but increasingly affecting society, conditioning the way people work and consume. The evident aspect of these transformations is the rapid multiplication of commonly used terms – such as gig , sharing , or platform – that have enriched the vocabulary of economics.

Nowadays, digital platforms are able to offer not just low value added services, as with home delivery, care work, or short-term rentals, but also skilled services performed by highly skilled workers such as engineers, accountants, and other professionals willing to provide services on an occasional basis.

With the rise of platforms, we are seeing not only an ever greater multiplication of occasional jobs, i.e. of work lacking any form of protection, but also a gradual platformization of the economy that risks expelling from the market anyone who is unable to adapt to those transformations.

It is increasingly evident that technological innovation is producing epochal transformations in the economy, not only making heretofore unthinkable organizational scenarios possible, but increasingly affecting society, conditioning the way people work and consume. The evident aspect of these transformations is the rapid multiplication of commonly used terms – such as gig, sharing, or platform – that have enriched the vocabulary of economics.

In many cases, however, given the contradictions of the processes that these words attempt to photograph, instead of clarifying, they often end up generating ambiguity due to their continuous overlapping. The goal of this brief contribution is to retrace the debate that has recently developed around those transformations, attempting to clarify some of the principal concepts that have become commonly used. More specifically, the goal is not only to define the margins within which the new trends operate, but also the relationships both between them, and with long-term processes of economic transformation.

First of all, we will present those socioeconomic factors that have led to the emergence of the gig economy, i.e. the gradual spread in recent years of occasional employment relationships. Secondly, we will clarify the impact of processes of digitalization, focusing in particular on the rise of digital platforms and their tendency to multiple these types of employment relationships. Lastly, we will discuss risks and opportunities that the spread of these phenomena implies both with regard to workers, and for traditional economic actors, and also for society as a whole. In conclusion, we will recall the need for regulation that is able to both promote and redistribute the benefits of technological development.

The rise of the gig economy

The “gig economy” is certainly among the terms that have spread the most in recent years, by which English-speaking literature has attempted to describe the expansion of occasional employment relationships. As Gerald Friedman notes, in particular starting with the financial crisis of 2007/2008:

“A growing number of American workers are no longer employed in ‘jobs’ with a long-term connection with a single company but are hired for ‘gigs’ under ‘flexible’ arrangements as ‘independent contractors’ or ‘consultants, ‘working only to complete a particular task or for defined time […].”[1]

The use of the word “gig” is significant, as it comes from the music world, where it is used to indicate the particular way musicians are hired, usually being compensated with a lump-sum for a single performance. What Friedman notices is that while in the past that form of compensation was reserved only to certain specific professions, today we find many to be in similar conditions: waiters, deliverymen, bricklayers, graphic designers, university professors, and numerous other professional figures, regardless of whether they are high or low skill workers.

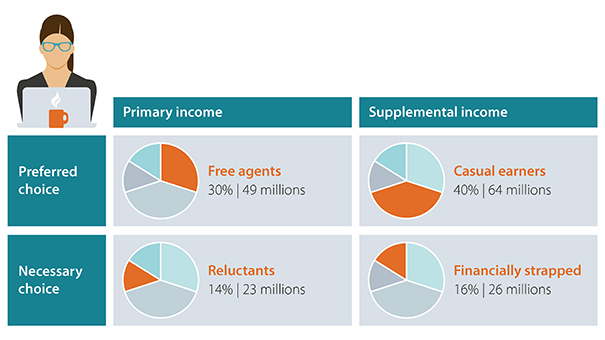

This growth has been photographed by the McKinsey Global Institute:[2] in a survey conducted in Europe and the United States based on over 8,000 questionnaires, it was found that over 160 million people, equal to between 20 and 30 percent of the total active population, habitually performs gigs.

What are the factors that have determined the growing spread of this type of employment? The study stresses that the varied nature of this segment of workers makes it difficult to identify a uniform trend behind the explosion of the gig economy. Therefore, as shown in Table 1, if on the one hand we can establish initial categories of those who perform occasional jobs as their primary source of income and those for whom occasional jobs are a source of supplementary income, on the other, these categories are intersected by the division between those who come to the gig economy as the result of a professional choice, and those who are motivated simply by necessity. In both cases, however, we see long-term trends that had begun to characterize economic transformations already before the advent of digital technologies.

Above all, for those who are “free agents” (people for whom occasional work is their principal source of income, who freely chose this type of employment relationship), we can see trends already observed by the researchers who in the 1990s focused on the transformation of independent work.[3] The current situation has similarities, because this group not only has a high level of education, but also greater satisfaction given by the value to the freedom this form of employment allows. In addition to the transformation of production, a decisive role in this case is played by cultural transformations that have led individuals to prefer employment free of temporal constraints, despite the fact that this implies exclusion from instruments of social protection.

However, that same component represents only one-third of the total composition of gig workers, a majority of whom perform occasional jobs as a way to supplement their principal source of income (we see this with “casual earners,” who do it by choice, and also of “financially strapped” individuals, who are forced to do such work). Thus the transformations that have taken place at the cultural level do not by themselves appear sufficient to explain the rapid growth of the gig economy. A decisive role is played by the material needs of individuals, such as the growth of unemployment or the gradual loss of purchasing power that has affected workers’ salaries across Western economies. Once again, Friedman observes:

“The gig economy expanded only when workers lost bargaining leverage with rising unemployment after the collapse of the internet boom. And the gig economy exploded with the economic collapse and the Great Recession.”[4]

The contraction of salaries, the increasing instability of the labor market, and the gradual reduction of welfare promoted at the policy level in recent years, are crucial among the factors that have favored the explosion of the gig economy. This is true above all as regards the component of “reluctants” (those for whom occasional jobs are the principal source of income, by necessity); since they are unable to find a stable job, they find a source of survival in the gig economy.

The performance of occasional work is thus not a new element produced by the digital era. This is even truer in Italy, where such activity has long been linked to the significant position that informal work occupies in our economy. The interest for the gig economy has multiplied considerably, though, following the continued spread of digital technologies. In recent years, we have seen exponential growth of digital platforms able to facilitate the encounter of supply and demand for occasional work services. Thus, although McKinsey estimates that just 15 percent of gig workers habitually make use of a digital platform, we can expect a rapid growth of these forms of work due to the spread of such tools.

Table 1 Share of working age population engaged in independent work

Source: James Manyika, Susan Lund, Jacques Bughin, Kelsey Robinson, Jan Mischke, Deepa Mahajan, Independent Work: Choice, Necessity, and the Gig Economy, McKinsey Global Institute, McKinsey & Company, October 2016, available online: www.mckinsey.com/global-themes/employment-and-growth/independent-work-choice-necessity-and-the-gig-economy.

From the sharing economy to the platform economy

The rise of digital platforms represents one of the most important consequences of what some authors have called the “new machine age.”[5] The spread of algorithms has in fact allowed for the formation of organizational infrastructure not only able to facilitate intermediation between supply and demand of goods and services, but that allows for reconfiguring those transactions around the centrality of the platform. Thus, especially in the initial phase of the debate, a substantial amount of literature developed around the ability of these technologies to give life to an economy based on the principle of sharing, i.e. an economy that departs from relations of a proprietary nature and rigid bonds of reciprocity. However, the definition of “sharing economy” quickly shows its ambiguity, since:

“according to an initial rigorous meaning, the expression “sharing economy” was reserved exclusively to those practices that are placed outside of the market […] but the same definition was used in a broader sense, to include market and profit models in which the platform earns from the intermediation activity, generally taking a commission on each transaction.”[6]

In recent years though, digital platforms have grown not only in number, but also in terms of market value, attracting larger investments and making the definition of sharing economy inadequate to represent the transformations underway. In such a scenario, more than simple infrastructure for intermediation placed at the margins of the market, platforms emerge as a distinct organizational model able to combine both the horizontal characteristics of the market, and the vertical nature of business. They become a particularly effective and efficient organizational structure that has rapidly asserted itself in the economic field, emerging as one of the hegemonic models.

Following that multiplication, there have also been numerous attempts to standardize the different types of platforms. Some have classified them based on their mission, dividing for-profit and non-profit platforms; some based on the type of transaction, i.e. whether paid or free, or starting with the diversity of the production process, differentiating between “crowdwork,” services performed remotely as happens for Amazon Mechanical Turk, and “work-on-demand,” as in the case of platforms for food delivery or care work[7] in which the service is performed in person. There are also those who have proposed more a detailed classification, such as Srnicek[8] for example, who starting with the way in which different platforms use the mass of data produced by interaction with users – the principal resource that moves the platform economy – created five different types. Apart from the single classification proposals, what interests us here is the extremely varied nature of the world of digital platforms; they are able to offer not just low value added services, as with home delivery, care work, or short-term rentals, but also skilled services performed by highly qualified workers such as engineers, accountants, and other professionals willing to provide services on an occasional basis.

In other words, the rapidity and variety with which platforms are developing makes the “platform economy” an umbrella expression able to indicate multiple types of transformations that at this time are impossible to uniformly define. Thus, if on the one hand this expansion expresses an actual trend towards platformization[9] of the economy, i.e. a general process of organizational transformation in response to technological innovation that involves a broadening sphere of businesses, on the other it risks once again generating ambiguity around the borders and meaning of the processes underway.

Risks and opportunities of the platform economy

The explosion of platforms, and of their conflicts with workers – in food delivery in particular – has stimulated a substantive debate also regarding the risks that their success entails. In particular, while on the one hand platforms are causing a formalization of activities historically carried out informally, on the other, workers seem to still be affected by those conditions of poverty and insecurity that characterize informal work. As Alex J Wood and his colleagues stress:

“Normative disembeddedness leaves workers exposed to the vagaries of the external labor market due to an absence of labor regulations and rights. It also endangers social reproduction by limiting access to healthcare and requiring workers to engage in significant unpaid ‘work-for-labor’.”[10]

The organizational model that characterizes platforms seems to evade the current structure of labor law. As the debate in this field indicates, platforms operate in a gray area lacking clear rules both in performing the service, and regarding the possibility for workers to have access to instruments of social protection. On the one hand, workers are forced operate under the direction of digital algorithms, thus having to face some of the typical risks of subordinate employment, while on the other, being classified as independent work prevents them from having the right to the protections associated with those risks. In other words, in the absence of regulation able to extend worker access to fundamental protections such as a minimum wage, injury protection, and labor union representation, the risk that the multiplication of platforms entails is that of a growth of the number of individuals who lack the possibility of access to social protection both inside and outside of the workplace.

However, this is not the only risk that the rise of digital platforms produces towards workers. Rather, the use of algorithms not only allows for the elusion of the traditional regulation of employment relationships, but also impacts the performance of the work itself, that tends to undergo a process of intensification. Again, Wood and his colleagues note:

“Algorithmic management techniques tend to offer workers high levels of flexibility, autonomy, task variety and complexity. However, these mechanisms of control can also result in low pay, social isolation, working unsocial and irregular hours, overwork, sleep deprivation and exhaustion.”[11]

In other words, the use of algorithms for functions such as monitoring work performance or the definition of classifications based on productivity not only risks shifting a significant portion of business risk to the workers, including risks linked to occupational injuries, but also ends up producing an increase of the same.

Yet workers are not the only ones who have to deal with the risks linked to the expansion of platforms. Given the lack of constraints on their activities, the effects of increasing concentration of power in the hands of platforms are also suffered by traditional economic actors such as restaurants and hotels. This is a process that not only reduces their profit margin while favoring the platforms, but that ends up creating a relationship of dependency that traditional economic actors are always hard pressed to avoid. Secondly, as the recent news of Amazon’s 600 million dollar investment in food delivery attests, significant transformations are also taking place inside the platform economy itself. While at the start it was populated by a galaxy of startups and small local financing, the current situation is characterized by multinational actors with considerable financial resources. The scenario that seems to emerge is that of a great war of platforms, where a few multinationals mobilize large resources with the goal of reaching a monopolistic position. In such a scenario, startups and local initiatives appear to have little margin for survival, thus risking being bought out or expelled from the market.

Despite those risks though, the potential offered by the exponential growth of technological development still appears largely unexplored. Indeed there are numerous experiences of “platform cooperativism,”[12] in which the goal is not only to create a redistribution of the organizational benefits of platforms, but also to socialize the ownership of the algorithms. So in the future, it will be increasingly necessary to pay attention to these types of experiences, that are already rapidly multiplying, but also obtaining increasingly promising market share.

So…

This brief contribution has attempted to clarify the ambiguity that has developed in the debate around the impact of technological innovation. This condition is above all the result of the contradictions involved, on the one hand offering unprecedented organizational opportunities, and on the other posing decisive challenges for the future of economy and work. With the rise of platforms, we are in fact seeing not only an ever greater multiplication of occasional jobs, i.e. of work lacking any form of protection, but also a gradual platformization of the economy that risks expelling from the market anyone who is unable to adapt to those transformations.

Despite this, technological development continues to expand the field of economic opportunity. However, to keep this space accessible and protect against possible risks, it is necessary to enact regulations that on the one hand can support continuous innovation, and on the other avoid potential negative impacts on the economy and work. In other words, it is only by redistributing the benefits of technological development, that is, by guaranteeing access to an increasing number of actors, that it is possible to imagine adapting society to the challenges it poses.

In brief

Even before the advent of digital technologies, we saw a multiplication of occasional work in high and low skilled professions. This process is rooted in both cultural and material factors, that on the one hand push individuals to increasingly search for this type of work, and on the other motivate businesses to use these forms of employment.

Initially, digital platforms were associated with a marginal component of the economy based on the principle of sharing. They not only proved to be able to generate market value, but represent a distinct organizational model able to operate in various sectors and destined to establish itself as a hegemonic model, expelling from the market everyone who is unable to adapt.

The success of digital platforms entails numerous risks: for workers, traditional economic actors, and also for startups and local projects, that now suffer competition from multinationals. Regulation is needed that not only limits the initiative of the platforms, but that is able to sustain technological innovation and redistribute its benefits in society.

G. Friedman, “Workers without employers: Shadow corporations and the rise of the gig economy,” Review of Keynesian Economics, 2(2), 2014, pp. 171-188

James Manyika, Susan Lund, Jacques Bughin, Kelsey Robinson, Jan Mischke, Deepa Mahajan, Independent Work: Choice, Necessity, and the Gig Economy, McKinsey Global Institute, McKinsey & Company, October 2016, available online: www.mckinsey.com/global-themes/employment-and-growth/independent-work-choice-necessity-and-the-gig-economy.

Among the various publications available on the issue, see, by way of example: S. Bologna, A. Fumagalli (editor), Il lavoro autonomo di seconda generazione, Milan, Feltrinelli, 1997.

Friedman, op. cit., p. 176.

E. Brynjolfsson, A. McAfee, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies, New Yok, W.W. Norton & Company, 2014.

G. Smorto, Sharing Economy e Modelli di Organizzazione, Paper presented at the Colloquio scientifico sull’impresa sociale, PAU Department (Heritage, Architecture, Urban Planning), Università degli Studi Mediterranea di Reggio Calabria, Reggio Calabria, May 22-23, 2015, p. 6.

V. De Stefano, “Crowdsourcing, The gig economy and the law”, Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal, 37, 2016, pp. 461-479.

N. Srnicek, Platform Capitalism, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2017.

T. Gillespie, “The politics of platforms”, New Media & Society, 12(3), 2010, pp. 347-364.

A. Wood et al., “Networked but commodified: The (dis)embeddedness of digital labour in the gig economy,” Sociology, 8/2/2019.

A.J. Wood et al., “Good gig, bad gig: Autonomy and algorithmic control in the global gig economy,” Work, Employment and Society, 33(1), pp. 56-75.

T. Scholz, Platform Cooperativism. Challenging the Corporate Sharing Economy, New York, Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, 2016.