Building the Future with Demography

Think future, build future. The strategies of companies, institutions, and corporations are based on approaches that project today onto tomorrow. Among these, one approach remains underutilized: the analysis of change through the lens of demography. Although demographic change may seem slow and almost imperceptible, this very phenomenon is one of the most powerful forces shaping our economic, social, and political future – a true megatrend. To envision the future and build a sustainable tomorrow, it is essential to adopt a demographic perspective. By starting with demography and then exploring the dynamics of human capital and markets, we aim to reflect on how both the slowness and inertia as well as the rapidity of demographic change profoundly affect the challenges ahead, with a particular focus on Italy.

Tomorrow is today: Slowness that builds the future

One of the most striking images to illustrate the influence of demography on our future is that of a clock's hands. This concept, introduced by the demographer and economist Alfred Sauvy, founder of the Institut National d'Études Démographiques in Paris (still the largest center for demographic studies in the world), captures the interplay between different societal forces. According to Sauvy, politics moves at the rapid pace of the second hand, often responding to successive emergencies with quick decisions. The economy, in turn, follows the rhythm of the minute hand, oscillating in short- and medium-term cycles influenced by both macroeconomic trends and the micro-level timing of business planning. However, we must also confront the apparent immobility of the hour hand, which represents demographics. Although it often escapes our attention, the "slowness" of the hour hand plays a key role in determining medium- to long-term trends.

Because of their inherent slowness, demographic phenomena often go unnoticed, yet they have profound consequences. Let's take a long-term perspective: in Italy, life expectancy in 1861 was only 29 to 30 years, while today it exceeds 83 years. Over the past century, advances in life expectancy have "gifted" us with about four additional months of life each year – equivalent to an extra eight hours a day! Similarly, global life expectancy has increased at a comparable rate over the past sixty years, and now averages 72 years. Although demographic change is slow, the increase in life expectancy has significantly shaped our identity today, highlighting the need for individuals, institutions, and companies to look toward the future. Yesterday's tomorrow is not today's, which is why we must be ready to embrace and manage this change.

Italy's example: From pyramids to ships

The transformation of Italy's demographic structure has been radical. In 1861, Italy was a youthful nation characterized by a population pyramid that was wide at the base and narrow at the top, indicating a growing population dominated by children. At that time, the elderly made up only a small part of the population, which consisted primarily of children, adolescents, and adults. Today, the situation is starkly different. By 2024, only 15.1% of the Italian population is under the age of 17, while 24.3% is over the age of 65. This shift is due not only to increased life expectancy, which places Italy among the top ten countries in the word in terms of longevity, but also to declining birth rates. This decline can be partially explained by a failure to adapt to gender diversity in society, particularly in the workplace, which requires a focus on shared parenting responsibilities.

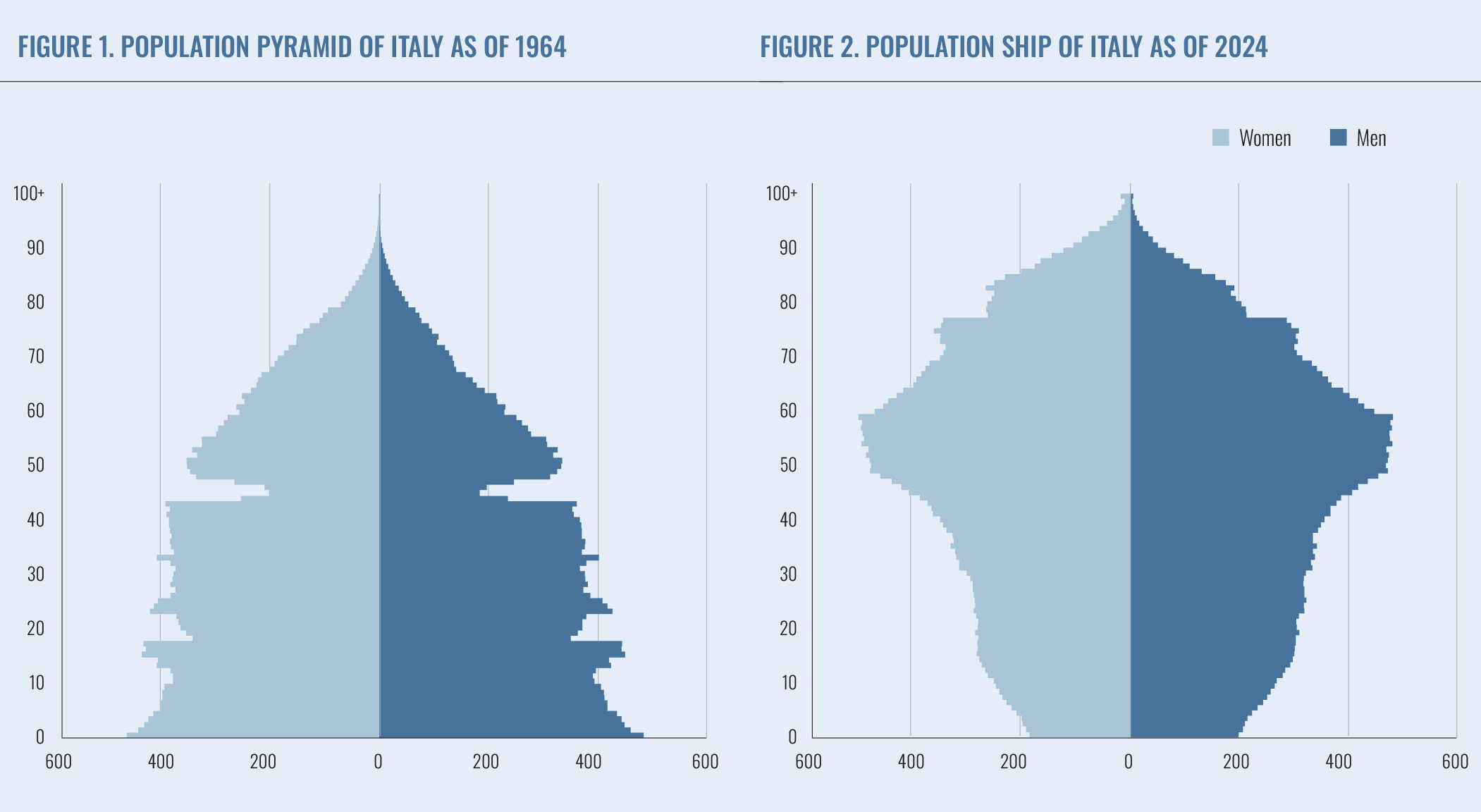

Specifically, Italy has experienced a dramatic decline in the number of births, from over one million in 1964 – that year still marks the peak of births and the sixty-year-old cohort is now the largest demographic group – to fewer than four hundred thousand in 2023. Consequently, the projected number of births in 2024 is likely to be about one-third of what it was sixty years ago. The population pyramid of 1964 (Figure 1), which showcases the legacy of that era, has now been transformed into a container ship seen from the stern in 2024 (Figure 2), with a marked reduction in the number of children and young people. As a result, Italy has become the third oldest country in the world, surpassed only by Monaco and Japan. Going forward, the ability to adapt and innovate in response to the challenges posed by global aging will be crucial.

Failure of human capital to adapt

For the first time in history, increased longevity has allowed multiple generations to live together simultaneously. This situation goes beyond the simple categories that marketing experts or family business analysts might use to describe different age groups. Instead, this demographic shift highlights how various generations interact within families, workplaces, and broader markets. What are the implications for human capital?

As life expectancy continues to rise, it is imperative that learning is seen as an integral part of our lives. This shift has led to the concept of lifelong learning, which is becoming increasingly important as we live longer. In addition, we must pay attention to the early stages of life, as they play a crucial role in the formation of human capital. Unfortunately, the institutions responsible for this education have not adapted to the transition from pyramids to ships. A notable example is Italy, where the Gentile reform of 1923, conceived when life expectancy was around 50 years, reserved higher education for a small elite.

Today, however, as we have observed, the base of the demographic ship is thinning, and we need an inclusive education system that prepares all young people for the challenges of an increasingly complex and globalized world. Human capital is built by starting at the base of the demographic ship and progressively moving to the higher "decks." With less than 30% of 25- to 34-year-olds in Italy holding a bachelor's degree, the country is at a disadvantage. As a result, the training needed to navigate the age of artificial intelligence inevitably demands a longer learning curve. By comparison, the average percentage of college graduates among young people in OECD countries exceeds 47%, while South Korea, which has the highest graduation rate in this age group, approaches 70%.

It is therefore crucial that Italy abandons the notion of an elitist education system and creates a framework that gives everyone, regardless of background, the opportunity to contribute to society. It is no coincidence that young Italians struggle to fully embrace adulthood. They lack access to university campuses, adequate housing policies, and a supportive social context that facilitates their journey to independence. As a result, many remain at home with their parents for much longer than their peers in other European countries, delaying their transition to adulthood and reducing their propensity to take risks and innovate during their formative years.

Migration and ethnic diversity: The risk of "permaemergency"

When discussing immigration, the term "state of emergency" is often used. Consider the Italian context: in recent decades, governments have declared a state of emergency on immigration no less than eight times, starting with the Andreotti government in 1992 and continuing with the Meloni government in 2023. This persistent state of emergency not only reflects Italy's struggles to manage migration flows, but also contributes to a narrative of instability and fear.

However, immigration is not a temporary problem that can be solved with emergency measures. It represents an extension of diversity, complementing the existing gender and generational diversity. The diversity of ethnic and cultural backgrounds is a reality that we must confront with foresight and inclusiveness. Today, nearly 9% of the Italian population is made up of foreign residents. Once known primarily as a country of emigration, Italy is now a destination for immigrants.

We can no longer afford to overlook this reality; instead, we must work to improve integration at all levels of our ethnically diverse society, particularly in the more economically advanced areas. Additionally, we must plan for orderly immigration flows that will help strengthen Italy's demographic landscape. In the coming decades, we should consider the Italian (and European) demographic landscape as complementary to the demographic pyramid of the Global South, which continues to have a substantial youth population. Notably, the global peak in birth rates occurred in 2012, with over 144 million births recorded that year.

Using the lens of demography: From public policy to the role of business

The ageing of the population and the coexistence of several generations as a result of long-term demographic changes; the evolution of family structures with declining birth rates and increasing gender diversity; the challenges faced by young people requiring a reassessment of human capital formation; the emergence of new ethnic diversity – these are all significant phenomena. Despite their complexity, these trends allow us to outline plausible future scenarios. Consequently, they demand innovative public policies at local, national, and supranational levels.

Companies, too, need to adopt a demographic perspective – not only to anticipate the current and future demands of markets characterized by strong and growing generational, gender, and ethnic diversity, but also to address the challenges posed by an aging population. Moreover, companies should look inward to capitalize on these diverse attributes and thereby increase productivity in a socially and environmentally sustainable manner.

References

Billari, F. (2023). Tomorrow is today. Building the future through the lens of demography, Egea, Milan.

Photo iStock / Ben Slater