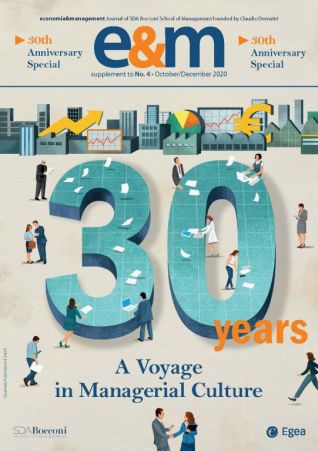

E&M

2020/5

Knowledge: A Factor for Competitiveness

Giudo Corbetta was the editor-in-chief of Economia&Management form 2014 to 2017. In this interview he retraces some of the fundamental points of his term, stressing the importance of training (studying and reading) for today's managers.