Creating value in global knowledge networks. Trust as a strategic lever for collaboration

Introduction

Imagine a meeting of fiercely competing Finnish telecom operators, major TV channels, a terminal manufacturer, information and communication technology (ICT) integrators and public-sector officials. They were all sitting together around a table, all deeply engaged in an open discussion about the potential of a new business opportunity. They collaborated intensively to co-create a systemic innovation integrating telecom networks, terminals, applications, and content. None of them alone had the required knowledge and resources, but together they came up with a highly complex system founded on interoperability and best-of-breed specialized knowledge. These Finnish engineers had learned to trust each other – after all, they all had technical backgrounds, spoke the same native and professional languages, and had known each other for a long time.

Imagine now the same time, same country, but a different industry – forestry. Key actors from Finnish paper manufacturers and machine suppliers knew each other personally; they went to university together and subsequently collaborated actively on basic research and in industry associations. Managers from competing firms regularly visited each other’s plants to learn about the latest developments, and then they went back to their own factories to improve their production lines and practices.

These scenes from the past are from the rather homogenous Finnish business context where engineers and managers collaborated thanks to mutual trust built on high social similarity, a shared past, and belief in a shared future. From the knowledge-based view of the firm (KBV), Finnish firms, in general, were able to share knowledge efficiently and effectively, continuously innovating and co-creating complex, knowledge-based products and services. Generalized trust towards others and interpersonal trust anchored on perceived competencies and goodwill made flexible knowledge sharing possible. Trustworthy behavior, a value-based norm, was socially controlled through dense interpersonal networks. Managers entering the field were socialized into industry practices and learned from their colleagues about how to balance collaboration with competition. In addition, the shadow of the future – both new business opportunities and the risk of being excluded from business networks – engendered natural incentives for trustworthy behavior. And finally, trusted institutions, such as universities and legal systems, provided a platform for inter-organizational and interpersonal interaction and knowledge sharing.

Much of today’s business collaboration occurs in a context quite different from what characterized a traditional local society: face-to-face interaction, social similarity, and familiarity. Globalization has challenged some of the well-established collaboration processes, offering less time and fewer opportunities for the incremental evolution of social and interpersonal trust nurtured by mutual recognition of competencies and goodwill. Social and physical distance, as well as transient and virtual relationships in international business, undermine the time and space needed for interpersonal trust to grow naturally. Consequently, in today’s global business environment, firms and individuals rely increasingly on impersonal and institutional trust underpinned by contracts, certified processes, and reputable institutions. Rapid technological change and unexpected exogenous shocks have accelerated this shift towards more impersonal trust-building mechanisms.

Our paper is motivated by a practical management challenge: how to forge value-creating trust in global knowledge collaboration where trust-building mechanisms based on shared past, social similarity, and familiarity are unavailable. Previous studies have shown that trust is critical for inter-organizational knowledge collaboration. Yet, collaboration performance stemming from knowledge co-creation has specific requirements that may not come naturally in the global context. Inspired by existing research findings and validated by a five-year case example, we argue that trust in global knowledge collaboration consists of hybrid characteristics that combine various elements of trust: interpersonal trust (local context) and impersonal trust (global environments); a generalized trusting attitude and object-specific trusting behavior; cognitive and affect-based trust; and trust grounded on reputation and action.

The paper proceeds as follows. First, we briefly outline how trust is viewed from a psychological, sociological, and economic perspective and put forward several key observations on the role and nature of trust in organizations. We then assert a set of propositions to develop a framework for building value-creating trust. We illustrate our framework by incorporating a well-known case of knowledge-based collaboration among a large community of firms in the international computer server market, and we conclude with implications for research and practice.

On the notion of trust in knowledge collaboration

The knowledge-based view of the firm rests on the premise that knowledge is critical for competitiveness and that the nature of knowledge production has implications for how it is shared and used. Tacit knowledge is more difficult to transfer than explicit knowledge. The latter requires less contextual understanding and socialization; transferring tacit knowledge typically requires personal interaction. Because individuals and organizations possess specialized knowledge developed through different experiences in different contexts, time and space are needed for people to connect and construct interpersonal trust in exchange relationships. Trust serves as an effective lubricant in managing uncertainty, vulnerability, complexity, information asymmetry, and related risks in exchange.

Researchers taking a psychological approach have focused on individuals, with particular interest in variations in human propensity (disposition) to trust and the attributes of trustworthy people. At the individual level, a trusting attitude is both a trait and a state, partly inherited and also learned from early childhood encounters about whom to trust. The capacity to trust and general optimism about the trustworthiness of others provide opportunities for beneficial interaction and enrich social learning about the trustworthiness of people and institutions. A generalized trusting attitude and positive human assumptions enhance willingness to take risks and interact socially.

For sociologists, trust has long been a central research topic. They focus on the collective level and see economic activity as socially embedded. Trust validates interpersonal exchange and coordination in collectives (communities, societies). Trust is an antecedent for reciprocity and collective action. In economics, trust lowers exchange costs, reduces transaction costs (search, negotiation, contracting, monitoring), and can increase exchange benefits; an actor’s reputation for trustworthiness may provide economic opportunities. Formal governance through contracting mitigates opportunism and functions as an impersonal substitute for experientially based trust.

Research on inter-organizational (inter-firm) trust has examined its antecedents, outcomes, and development. Here we define trustworthiness as an actor’s expectation of the counterpart’s competence, goodwill, and identity (persons and firm). Our definition emphasizes value creation in knowledge collaboration (by adding competence) and incorporates interpersonal and organizational sources of trust.

In knowledge collaboration, relevant competence (technical knowledge, skills, know-how) is a key antecedent of trust; access to complementary knowledge and resources motivates cooperation. Signs of goodwill (moral responsibility, positive intentions) enable acceptance of risk and vulnerability in knowledge sharing. Identity reflects an actor’s referential understanding; at the firm level, identity is expressed in corporate values and strategy. The dimensions (competence, goodwill, identity) are additive and apply at both interpersonal and inter-organizational levels.

Social and impersonal trust referents in inter-firm relationships

Inter-firm trust combines social, interpersonal, and impersonal trust elements. It operates through impersonal trust in structures and processes, and social trust in relationships among boundary-spanners. Interpersonal trust is essential for knowledge sharing because knowledge is personal and sharing it entails vulnerability; it supports both tacit knowledge sharing and use. Interpersonal trust also supports the evolution of inter-firm trust, and vice versa: credible impersonal trust referents can transfer into interpersonal trust. Impersonal referents include products, services, processes, culture, routines, and institutionalized practices; impersonal trust is built via trustworthiness cues from systems rather than people.

Cognition-based and affect-based trust in knowledge collaboration

The cognitive and affective foundations of trust are well established. Cognition involves perception, reasoning, and judgement. Cognition-based trust is grounded in rational reasoning and evidence; it reflects trust in competence and supports positive analytical evaluation, affecting knowledge collaboration performance and encouraging knowledge-seeking and investment in the relationship. Affect-based trust stems from personal values and emotional ties, involving care and concern; it supports better information exchange, extra-role behavior, more cooperative strategies, stronger trust, and fuels creativity and divergent thinking. Affect-based trust is critical for knowledge sharing, while cognitive trust is more salient in knowledge use. Affect-based trust takes more time to develop; cognitive trust rests on formal roles, role-prescribed behavior, and enlightened self-interest, while affect-based trust rests on extra-role and person-specific behavior and the virtue of relationships.

Generalized and specific trust across cultures

A generalized willingness to trust is partly a personality trait, shaped by life experiences; trust varies across cultures due to norms, values, and institutions. Higher generalized trust is common in Scandinavia, associated with favorable social conditions, equitable income distribution, low perceived corruption, and institutional mechanisms like legal safeguards. Generalized trust fosters openness to new people and situations; it is lower in contexts such as Turkey, Brazil, and China. Cultural differences (collectivist vs individualistic) shape trust: in collectivist cultures, trust and loyalty develop within in-groups; in Russia, trust is often particularistic; in China, guanxi (close ties, mutual affect, opportunity) can outweigh impersonal institutional trust. In more individualistic countries (e.g., Germany, Finland), generalized trust and impersonal trust-building mechanisms may be relatively more important in business relationships.

Trust as attitude, decision, and behavior

Trust often develops incrementally through gradual investments. Reputation signals trustworthiness and can yield business opportunities in dense networks. In global knowledge collaboration, a trusting attitude and trustworthy reputation (individual and organizational) can be threshold conditions for exchange and sources of firm performance. But scholars call for a more active approach: trust-implying actions and relation-specific investments signal willingness to trust and commitment. Active trusting behavior is especially meaningful in global and virtual contexts, where familiarity, social similarity, and continuous interaction are limited.

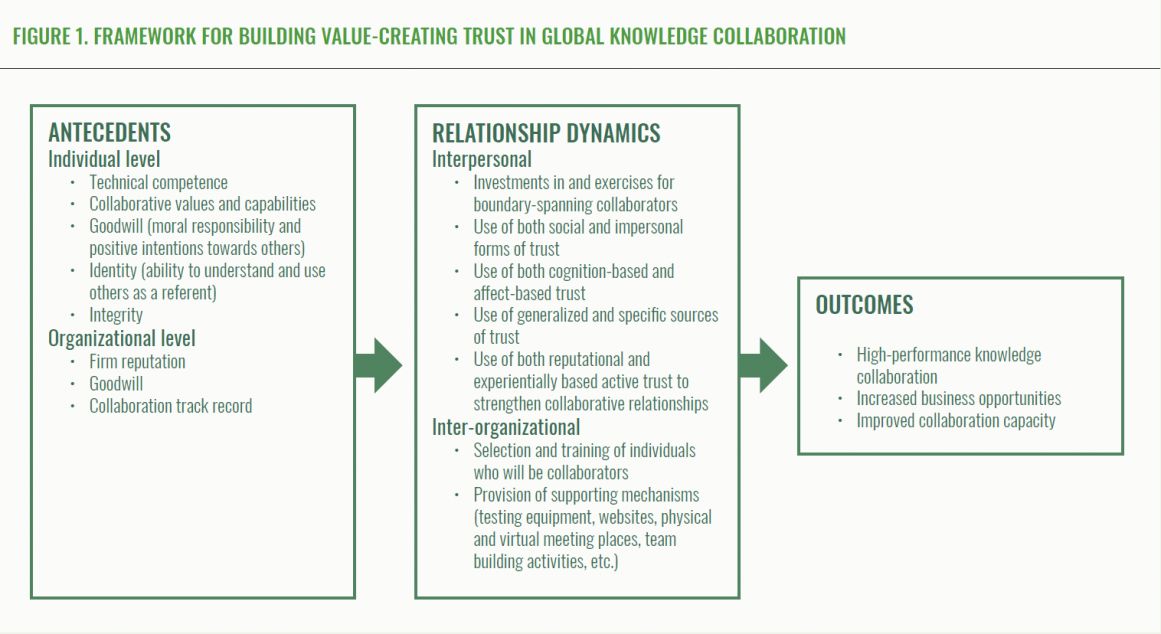

Framework for building value-creating trust

We propose a hybrid framework of value-creating inter-organizational trust, summarized in Table 1, combining:

-

Forms of trust: social, impersonal, social and impersonal

-

Bases of trust: affect-based, cognitive, affect- and cognition-based

-

Sources of trust: generalized, specific, generalized trusting attitude and specific behavior

-

Development of trust: reputational, action-based, reputation- and action-based

Forms of trust: social and impersonal

Interpersonal (social) trust is critical for value creation in knowledge collaboration but insufficient/less available globally (no shared past, limited shadow of the future, distance, rotation across roles/locations). Hence, interpersonal trust must be reinforced by impersonal trust (trust in strategy, brand, contracts, certifications, processes, culture, structures).

Proposition 1: Positive synergy in global knowledge collaboration comes from combining interpersonal and impersonal trust, not either alone.

Bases of trust: cognition-based and affect-based

Cognition-based trust is analytical and rational (competence, track record, relevant knowledge). Affect-based trust supports vulnerability and is suited to complex collaboration requiring tacit knowledge and intrinsic motivation, but can be riskier if not balanced by cognition-based trust. Both are needed for value-creating trust.

Proposition 2: Positive synergy comes from combining affect-based and cognition-based trust, not either alone.

Sources of trust: generalized trusting attitude and object-specific trusting behavior

A generalized trusting attitude enables access to non-redundant knowledge/resources via weak ties and supports initiating new relationships; it can reduce transaction costs and increase benefits. However, generalized trust can be risky in low-trust contexts, and purely particularistic trust can limit access to dispersed knowledge and inhibit innovation and renewal. Actual trust must include object-specific trusting behavior: context-specific risk-taking decisions/actions (e.g., disclosure of sensitive information).

Proposition 3: Positive synergy comes from combining generalized and object-specific trust, not either alone.

Development of trust: reputational and action-based

Reputation is crucial in technology-enabled global networks; it reduces transaction costs and opens business opportunities (e.g., R&D, standardization). Global knowledge collaboration also requires fast trust built quickly through action; performance-based trust (e.g., Silicon Valley) depends on recent performance and reputation, open to outsiders and diverse backgrounds. Fast trust can be a “risky investment” but can yield profitable opportunities. Action-based trust protects reputation and requires active analytical evaluation of capability, goodwill, and identity.

Proposition 4: Positive synergy comes from combining reputational and experientially/action-based trust, not either alone.

Blade.org: trust dynamics in a global collaborative community

Blade.org (international computer server market) was established in 2006 by IBM and seven other founding firms to support IBM BladeCenter. It formed a community of complementor companies to accelerate development and commercialization of blade-based solutions. Membership grew from invited firms (27 → 70) to more than 200 firms. The community had nine technical committees (technology, solutions architecture, compliance and interoperability, power and cooling). Projects were typically carried out by two to four companies. A Principal Office provided infrastructure, administrative services, and strategic initiatives—critical for building impersonal trust. In the first 18 months, firms developed more than 60 solutions.

At the interpersonal level, trust emerged through repeated interaction in committees; participants (“Blade people”) self-selected due to collaboration interest/ability. Task-oriented interactions enabled assessment of competence and reliability, fostering interpersonal trust grounded in ability, benevolence, and integrity. Interpersonal ties acted as conduits for knowledge sharing and inter-organizational trust; accumulated success built a reputation for trustworthiness, safeguarding against opportunism and reinforcing credible collaboration. Trust was intentionally cultivated through design at individual, organizational, and community levels, combining generalized attitude and specific behavior, supported by mechanisms enabling trust without hierarchical control.

Managerial Impact Factor

• Design hybrid trust systems: Combine interpersonal and institutional mechanisms to sustain collaboration across global and virtual contexts.

• Balance cognition and emotion: Foster analytical evaluation (competence) and affective bonds (goodwill) to enhance knowledge sharing.

• Promote generalized openness: Encourage a trusting attitude toward diverse partners while maintaining context-specific risk assessment.

• Build and act on reputation: Strengthen organizational credibility through consistent, trustworthy behavior and transparent performance.

• Empower boundary-spanners: Select and train individuals skilled in cross-cultural communication and collaborative problem-solving.

• Create enabling structures: Establish platforms, forums, and routines that institutionalize trust and facilitate rapid, reliable cooperation.

References

- Adler, P. (2001). “Market, hierarchy, and trust: The knowledge economy and the future of capitalism.” Organization Science, 12(2), 215–234.

- American Psychological Association (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). American Psychological Association.

- Argote, L., McEvily, B., Reagans, R. (2003). “Managing knowledge in organizations: An integrative framework and review of emerging themes.” Management Science, 49(4), 571–582.

- Ariño, A., de la Torre, J., Ring, P.S. (2001). “Relational quality: Managing trust in corporate alliances.” California Management Review, 44(1), 109–131.

- Arrow, K. (1974). Limits of economic organization. Norton.

- Ashnai, B., Henneberg, S.C., Naudé, P., Francescucci, A. (2016). “Inter-personal and inter-organizational trust in business relationships: An attitude–behavior–outcome model.” Industrial Marketing Management, 52, 128–139.

- Axelrod, R. (1984). The evolution of cooperation. Basic Books.

- Bachmann, R. (2006). “Trust and/or power: Towards a sociological theory of organizational relationships.” In Bachmann, R., Zaheer, A. (Eds.), Handbook of trust research (pp. 393–408). Edward Elgar.

- Bachmann, R. (2011). “At the crossroads: Future directions in trust research.” Journal of Trust Research, 1(2), 203–213.

- Baer, M.D., et al. (2018). “It’s not you, it’s them: Social influences on trust propensity and trust dynamics.” Personnel Psychology, 71(3), 423–455.

- Barney, J.B., Hansen, M.H. (1994). “Trustworthiness as a source of competitive advantage.” Strategic Management Journal, 15, 175–190.

- Becerra, M., Lunnan, R., Huemer, L. (2008). “Trustworthiness, risk, and the transfer of tacit and explicit knowledge between alliance partners.” Journal of Management Studies, 45(4), 691–713.

- Blau, P.M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

- Blomqvist, K. (1997). “The many faces of trust.” Scandinavian Journal of Management, 13(3), 271–286.

- Blomqvist, K. (2002). Partnering in the dynamic environment: The role of trust in asymmetric technology partnership formation (Acta Universitatis Lappeenrantaensis 122).

- Blomqvist, K. (2005). “Trust in a dynamic environment: Fast trust as a threshold condition for asymmetric technology partnership formation in the ICT sector.” In Bijlsma-Frankema, K.M., Klein Woolthuis, R.J.A. (Eds.), Trust under pressure: Empirical investigations of the functioning of trust and trust building in uncertain circumstances (pp. 208–234). Edward Elgar.

- Blomqvist, K., Cook, K. (2018). “Swift trust: State of the art and future research directions.” In Searle, R., Nienaber, A.M., Sitkin, S.B. (Eds.), The Routledge companion to trust (pp. 29–49). Routledge.

- Blomqvist, K., Cook, K.S. (2026). “Trust transfer.” In Schafheitle, S., Van der Werff, L., Hamm, J.A. (Eds.), Trust encyclopedia (forthcoming).

- Blomqvist, K., Hurmelinna, P., Seppänen, R. (2005). “Playing the collaboration game right: Balancing trust and contracting.” Technovation, 25(5), 497–504.

- Blomqvist, K., Kyläheiko, K., Virolainen, V. (2002). “Filling the gap in traditional transaction cost economics: Towards transaction benefits–based analysis using Finnish telecommunications as an illustration.” International Journal of Production Economics, 70, 1–14.

- Blomqvist, K., et al. (2007). Hybrid Innovation Management- Lessons Learned from Mobile TV Development. Presented at Berkeley Service Innovation Conference, Berkeley, April 26-27.

- Boisot, M., Child, J. (1996). “From fiefs to clans and network capitalism: Explaining China’s emerging economic order.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 600–628.

- Buckley, P.J., Clegg, J., Tan, H. (2006). “Cultural awareness in knowledge transfer to China: The role of guanxi and mianzi.” Journal of World Business, 41(3), 275–288.

- Burt, R.S. (1992). Structural holes. Harvard University Press.

- Burt, R.S. (2000). “The network structure of social capital.” In Sutton, R.I., Staw, B.M. (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (pp. 345–423). JAI Press.

- Burt, R.S., Knez, M. (1996). “Trust and third-party gossip.” In Kramer, R.M., Tyler, T.R. (Eds.), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research (pp. 68–89). Sage.

- Castaldo, S., Premazzi, K., Zerbini, F. (2010). “The meaning(s) of trust: A content analysis on the diverse conceptualizations of trust in scholarly research on business relationships.” Journal of Business Ethics, 96(4), 657–668.

- Child, J. (2001). “Trust: The fundamental bond in global collaboration.” Organizational Dynamics, 29(4), 274–288.

- Child, J., Möllering, G. (2003). “Contextual confidence and active trust development in the Chinese business environment.” Organization Science, 14(1), 69–80.

- Chowdhury, S. (2005). “The role of affect- and cognition-based trust in complex knowledge sharing.” Journal of Managerial Issues, 17(3), 310–326.

- Chua, R.Y., Morris, M.W., Mor, S. (2012). “Collaborating across cultures: Cultural metacognition and affect-based trust in creative collaboration.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 118(2), 116–131.

- Cohen, S.S., Fields, G. (2000). “Social capital and capital gains: An examination of social capital in Silicon Valley.” In Kenney, M. (Ed.), Understanding Silicon Valley: The anatomy of an entrepreneurial region (pp. 266–292). Stanford University Press.

- Cook, K.S., Hardin, R., Levi, M. (2005). “The significance of trust.” In Cook, K.S., Hardin, R., Levi, M. (Eds.), Cooperation without trust? (pp. 1–19). Russell Sage Foundation.

- Cullen, J.B., Johnson, J.L., Sakano, T. (2000). “Success through commitment and trust: The soft side of strategic alliance management.” Journal of World Business, 35(3), 223–240.

- Currall, S.C., Inkpen, A.C. (2002). “A multilevel approach to trust in joint ventures.” Journal of International Business Studies, 33, 479–495.

- Currall, S.C., Judge, T. A. (1995). “Measuring trust between organizational boundary role persons.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 64(2), 151–170.

- Dhanaraj, C., et al. (2004). “Managing tacit and explicit knowledge transfer in IJVs: The role of relational embeddedness and the impact on performance.” Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5), 428–442.

- Dietz, G., den Hartog, D. (2006). “Measuring trust inside organisations.” Personnel Review, 35(5), 557–588.

- Dietz, G., Gillespie, N., Chao, G. (2010). “Introduction: Unravelling the complexities of trust and culture.” In Saunders, M.N.K., et al. (Eds.), Organizational trust: A cultural perspective (pp. 3–41). Cambridge University Press.

- Dirks, K.T., Ferrin, D. (2001). “The role of trust in organizational settings.” Organization Science, 12, 450–467.

- Doney, P.M., Cannon, J.P. (1997). “An examination of the nature of trust in buyer–seller relationships.” Journal of Marketing, 61, 35–51.

- Dyer, J.H., Chu, W. (2000). “The determinants of trust in supplier–automaker relationships in the U.S., Japan and Korea.” Journal of International Business Studies, 31, 259–285.

- Dyer, J.H., Chu, W. (2003). “The role of trustworthiness in reducing transaction costs and improving performance: Empirical evidence from the United States, Japan, and Korea.” Organization Science, 14(1), 57–68.

- Dyer, J.H., Chu, W. (2011). “The determinants of trust in supplier–automaker relations in the U.S., Japan, and Korea: A retrospective.” Journal of International Business Studies, 42(1), 28–34.

- Dyer, J.H., Singh, H. (1998). “The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage.” Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 660–679.

- Elfenbein, H.A. (2023). “Emotion in organizations: Theory and research.” Annual Review of Psychology, 74(1), 489–517.

- Erikson, E.H. (1963). Childhood and society (2nd ed.). W. W. Norton.

- Ferrin, D., Gillespie, N. (2010). Trust differences across national–societal cultures: Much to do, or much ado about nothing? In Saunders, M.N.K. et al. (Eds.), Organizational trust: A cultural perspective (pp. 42–86). Cambridge University Press.

- Fjeldstad, Ø.D., et al. (2012). The architecture of collaboration. Strategic Management Journal, 33(6), 734–750.

- Foss, N. J. (1996). “Knowledge-based approaches to the theory of the firm: Some critical comments.” Organization Science, 7(5), 470–476.

- Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. Free Press.

- Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Stanford University Press.

- Gillespie, N., Dietz, G. (2009). “Trust repair after an organization-level failure.” Academy of Management Review, 34(1), 127–145.

- Granovetter, M. (1973). “The strength of weak ties.” American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380.

- Granovetter, M. (1985). “Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness.” American Journal of Sociology, 91, 481–510.

- Grant, R. (1996). “Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm.” Strategic Management Journal, 17, 109–122.

- Grant, R.M. (2013). “Reflections on knowledge-based approaches to the organization of production.” Journal of Management & Governance, 17, 541–558.

- Grant, R.M., Baden-Fuller, C. (2004). “A knowledge accessing theory of strategic alliances.” Journal of Management Studies, 41(1), 61–84.

- Grant, R., Phene, A. (2022). “The knowledge-based view and global strategy: Past impact and future potential.” Global Strategy Journal, 12(1), 3–30.

- Griffith, D.A. (2002). “Role of communication competencies in international business relationship development.” Journal of World Business, 37(4), 256–265.

- Gulati, R. (1995). “Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repeated ties for contractual choice in alliances.” Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 85–112.

- Gulati, R. (1998). “Alliances and networks.” Strategic Management Journal, 19(4), 293–317.

- Hardin, R. (1993). “The street-level epistemology of trust.” Politics & Society, 21(4), 505–529.

- Hayashi, N., et al. (1999). “Reciprocity, trust, and the sense of control: A cross-societal study.” Rationality and Society, 11, 27–46.

- Henttonen, K., Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P., Blomqvist, K. (2020). “Between trust and control in R&D alliances.” VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 50(2), 247–269.

- Holste, J.S., Fields, D. (2010). “Trust and tacit knowledge sharing and use.” Journal of Knowledge Management, 14(1), 128–140.

- Huang, Q., Davison, R.M., Gu, J. (2008). “Impact of personal and cultural factors on knowledge sharing in China.” Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 25, 451–471.

- Huff, L., Kelley, L. (2003). “Levels of organizational trust in individualist versus collectivist societies: A seven-nation study.” Organization Science, 14(1), 81–90.

- Huff, L., Kelley, L. (2005). “Is collectivism a liability? The impact of culture on organizational trust and customer orientation: A seven-nation study.” Journal of Business Research, 58(1), 96–102.

- Hurmelinna, P., et al. (2006). “Striving towards R&D collaboration performance: The effect of asymmetry, trust, and contracting.” Creativity and Innovation Management, 14(4), 374–383.

- Jarvenpaa, S.L., Leidner, D.E. (1999). “Communication and trust in global virtual teams.” Organization Science, 10(6), 791–815.

- Jones, G.R., George, J.M. (1998). “The experience and evolution of trust: Implications for cooperation and teamwork.” Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 531–546.

- Jukka, M., Blomqvist, K., Li, P.P., Gan, C. (2017). “Trust–distrust balance: Trust ambivalence in Sino-Western B2B relationships.” Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 24(3), 482–507.

- Kasper-Fuehrer, E.C., Ashkanasy, N.M. (2001). “Communicating trustworthiness and building trust in inter-organizational virtual organizations.” Journal of Management, 27, 235–354.

- Kenney, M. (2000). “Introduction.” In M. Kenney (Ed.), Understanding Silicon Valley: The anatomy of an entrepreneurial region (pp. 1–12). Stanford University Press.

- Kern, H. (1998). “Lack of trust, surfeit of trust: Some causes of the innovation crisis in German industry.” In Lane, C., Bachmann, R. (Eds.), Trust within and between organizations (pp. 203–213). Oxford University Press.

- Kogut, B., Zander, U. (1992). “Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology.” Organization Science, 3(3), 383–397.

- Kollock, P. (1994). “The emergence of exchange structures: An experimental study of uncertainty, commitment, and trust.” American Journal of Sociology, 100(2), 313–345.

- Kramer, R.M. (1999). “Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions.” Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 569–598.

- Kramer, R.M. (2006). “Organizational trust: Progress and promise in theory and research.” In Kramer, R.M. (Ed.), Organizational trust: A reader (pp. 21–47). Oxford University Press.

- Kramer, R.M., Brewer, M., Hanna, B. (1996). “Collective trust and collective action: The decision to trust as a social decision.” In Kramer, R.M., Tyler, T.R. (Eds.), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research (pp. 357–389). Sage.

- Krishnan, R., Martin, X., Noorderhaven, N.G. (2006). “When does trust matter to alliance performance?” Academy of Management Journal, 49(5), 894–917.

- Kroeger, F. (2019). “Unlocking the treasure trove: How can Luhmann’s theory of trust enrich trust research?” Journal of Trust Research, 9(1), 110–124.

- Lane, C. (1998). “Theories and issues in the study of trust.” In Lane, C., Bachmann, R. (Eds.), Trust within and between organizations (pp. 1–13). Oxford University Press.

- Lane, C., Bachmann, R. (1996). “The social constitution of trust: Supplier relations in Britain and Germany.” Organization Studies, 17(3), 365–395.

- Lewicki, R.J., Bunker, B.B. (1995). “Trust in relationships: A model of development and decline.” In Bunker, B.B., Rubin, J.Z. (Eds.), Conflict, cooperation, and justice: Essays inspired by the work of Morton Deutsch (pp. 133–173). Jossey-Bass.

- Lewicki, R.J., McAllister, D.J., Bies, R.J. (1998). “Trust and distrust: New relationships and realities.” Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 438–458.

- Lewis, J.D., Weigert, A. (1985). “Trust as a social reality.” Social Forces, 63(4), 967–985.

- Li, J.J., Poppo, L., Zhou, K.Z. (2010). “Relational mechanisms, formal contracts, and local knowledge acquisition by international subsidiaries.” Strategic Management Journal, 31(4), 349–370.

- Li, P.P. (2008). “Toward a geocentric framework of trust: An application to organizational trust.” Management and Organization Review, 4(3), 413–439.

- Luhmann, N. (1979). Trust and power. Wiley.

- Lumineau, F., Schilke, O., Wang, W. (2023). “Organizational trust in the age of the fourth industrial revolution: Shifts in the form, production, and targets of trust.” Journal of Management Inquiry, 32(1), 21–34.

- Malhotra, A. (2021). “The postpandemic future of work.” Journal of Management, 47(5), 1091–1102.

- Mayer, R.C., Davis, J.H., Schoorman, F.D. (1995). “An integrative model of organizational trust.” Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734.

- McAllister, D.J. (1995). “Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations.” Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 24–59.

- McEvily, B., Tortoriello, M. (2011). “Measuring trust in organisational research: Review and recommendations.” Journal of Trust Research, 1(1), 23–63.

- McEvily, B., Zaheer, A. (2006). “Does trust still matter? Research on the role of trust in inter-organizational exchange.” In Bachmann, R., Zaheer, A. (Eds.), Handbook of trust research (pp. 280–300). Edward Elgar.

- McEvily, B., Perrone, V., Zaheer, A. (2003). “Trust as an organizing principle.” Organization Science, 14(1), 91–103.

- Meyerson, D., Weick, K.E., Kramer, R.M. (1996). “Swift trust and temporary groups.” In Kramer, R.M., Tyler, T.R. (Eds.), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research (pp. 166–195). Sage.

- Michailova, S., Husted, K. (2003). “Knowledge sharing hostility in Russian firms.” California Management Review, 45(3), 59–77.

- Michailova, S., Hutchings, K. (2006). “National cultural influences on knowledge sharing: A comparison of China and Russia.” Journal of Management Studies, 43(3), 383–405.

- Michailova, S., Worm, V. (2003). “Personal networking in Russia and China: Blat and guanxi.” European Management Journal, 21(4), 509–519.

- Miles, R.E., Miles, G., Snow, C.C. (2005). Collaborative entrepreneurship: How communities of networked firms use continuous innovation to create economic wealth. Stanford University Press.

- Miles, R.E., et al. (2009). “The I-Form organization.” California Management Review, 51(4), 59–74.

- Miles, R.E., Snow, C.C., Miles, G. (2000). “TheFuture.org.” Long Range Planning, 33, 300–321.

- Möllering, G. (2006). “Trust beyond risk: The leap of faith.” In Trust: Reason, routine, reflexivity (pp. 105–126). Elsevier.

- Nahapiet, J., Ghoshal, S. (1998). “Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage.” Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266.

- Nonaka, I. (1994). “A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation.” Organization Science, 5(1), 14–37.

- Nonaka, I., Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. Oxford University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (1998). “A behavioral approach to the rational choice theory of collective action: Presidential address, American Political Science Association, 1997.” American Political Science Review, 92, 1–22.

- Polanyi, M. (1962). Personal knowledge. University of Chicago Press.

- Portes, A. (1998). “Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 1–24.

- Reimann, M., Schilke, O., Cook, K.S. (2017). “Trust is heritable, whereas distrust is not.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(27), 7007–7012.

- Ring, P.S., Van de Ven, A.H. (1992). “Structuring cooperative relationships between organizations.” Strategic Management Journal, 13(7), 483–498.

- Ring, P.S., Van de Ven, A.H. (1994). “Developmental processes of cooperative interorganizational relationships.” Academy of Management Review, 19(1), 90–118.

- Ritala, P., Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P., Blomqvist, K. (2009). “Tug of war in innovation coopetitive service development.” International Journal of Services Technology and Management, 12(3), 255–272.

- Robinson, S.L., Dirks, K.T., Özçelik, H. (2004). “Untangling the knot of trust and betrayal.” In Kramer, R.M., Cook, K.S. (Eds.), Trust and distrust in organizations: Dilemmas and approaches (pp. 327–341). Russell Sage Foundation.

- Rocha, H., Ghoshal, S. (2006). “Beyond self-interest revisited.” Journal of Management Studies, 43(3), 585–619.

- Rothstein, B., Stolle, D. (2003). “Introduction: Social capital in Scandinavia.” Scandinavian Political Studies, 26(1), 1–26.

- Rotter, J.B. (1971). “Generalized expectancies for interpersonal trust.” American Psychologist, 26, 443–452.

- Rousseau, D.M., et al. (1998). “Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust.” Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393–404.

- Saunders, M.N.K., Skinner, D., Lewicki, R.J. (2010). “Conclusions and ways forward.” In Saunders, M.N.K., (Eds.), Organizational trust: A cultural perspective (pp. 407–423). Cambridge University Press.

- Schilke, O., Cook, K.S. (2013). “A cross-level process theory of trust development in interorganizational relationships.” Strategic Organization, 11(3), 281–303.

- Schilke, O., Reimann, M., Cook, K.S. (2021). “Trust in social relations.” Annual Review of Sociology, 47, 239–259.

- Scott, S.V., Walsham, G. (2005). “Reconceptualizing and managing reputation risk in the knowledge economy: Toward reputable action.” Organization Science, 16(3), 308–322.

- Seppänen, R. (2008). Trust in inter-organizational relationship (Acta Universitatis Lappeenrantaensis 328).

- Seppänen, R., Blomqvist, K., Sundqvist, S. (2007). “Measuring inter-organizational trust: A critical review of the empirical research in 1990–2003.” Industrial Marketing Management, 36, 249–265.

- Shapiro, S. (1987). “The social control of impersonal trust.” American Journal of Sociology, 93(3), 623–658.

- Snow, C. C., et al. (2011). “Organizing continuous product development and commercialization: The collaborative community of firms model.” Journal of Product Innovation Management, 28, 3–16.

- Stewart, K. J. (2003). “Trust transfer on the World Wide Web.” Organization Science, 14(1), 5–17.

- Szulanski, G. (2003). Sticky knowledge: Barriers to knowing in the firm. Sage.

- Uslaner, E. (2010). Corruption, inequality, and the rule of law. Cambridge University Press.

- Uzzi, B. (1996). “Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: The paradox of embeddedness.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 37–69.

- Uzzi, B., Spiro, J. (2005). “Collaboration and creativity: The small-world problem.” American Journal of Sociology, 111(2), 447–504.

- Van de Ven, A.H. (1976). “On the nature, formation and maintenance of relations among organizations.” Academy of Management Review, 1(4), 24–36.

- Van Lange, P.A. (2015). “Generalized trust: Four lessons from genetics and culture.” Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(1), 71–76.

- Vanhala, M., Puumalainen, K., Blomqvist, K. (2011). “Impersonal trust: The development of the construct and the scale.” Personnel Review, 40(4), 485–513.

- von Krogh, G., Ichijo, K., Nonaka, I. (2000). Enabling knowledge creation: How to unlock the mystery of tacit knowledge and release the power of innovation. Oxford University Press.

- Wicks, A.C., Berman, S.L., Jones, T.M. (1999). “The structure of optimal trust: Moral and strategic implications.” Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 99–116.

- Williams, M. (2007). “Building genuine trust through interpersonal emotion management: A threat regulation model of trust and collaboration across boundaries.” Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 595–621.

- Williamson, O.E. (1993). “Calculativeness, trust, and economic organization.” Journal of Law and Economics, 36, 453–486.

- Yamagishi, T. (2011). Trust: The evolutionary game of mind and society. Springer.

- Zaheer, A., McEvily, B., Perrone, V. (1998). “Does trust matter? Exploring the effects of inter-organizational and interpersonal trust on performance.” Organization Science, 9(2), 141–159.

- Zaheer, S., Zaheer, A. (2006). “Trust across borders.” Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 21–29.

Photo iStock / Tanatpon Chaweewat